No Ke Kanikau | On Kanikau

A conversation with

Puakea Nogelmeier

No ka Mahina o Ka ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, 2019, ua koho ʻia akula ke kanikau ʻo ia kekahi mea e noiʻi a unihi ʻia no ka hōʻike ʻana ma Kealopiko Moʻolelo nei. I mea hoʻi e hoʻokahua ai i koʻu hoʻomaopopo ʻana i ia mea he kanikau, kamaʻilio akula māua ʻo kuʻu kumu unihi, ʻo Puakea Nogelmeier no kēia kumuhana nui wale o ka hoihoi. ʻO nā māhele ʻono loa o kā māua wahi kole, aia nō ma lalo nei.

For Hawaiian language month 2019, kanikau is one of the subjects that was chosen for research and translation to present here on Kealopiko Stories. To build a foundation for my own understanding of kanikau, I had a chat with my translation teacher Puakea Nogelmeier on this fascinating subject. Below is the best of our conversation in both ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and English.

**************************************

Hina: He aha ia mea he kanikau?

Hina: What is a kanikau?

Puakea: He ʻano mele – he oli – e hōʻike ana i ke aloha a me ka pilina i kekahi kanaka, ka mea maʻamau i kahi mea i hala aku i ka make, i ka hoʻi ʻole mai. I kekahi manawa, hiki ke hana ʻia i ka haʻalele ʻana o kekahi, me ka ʻike e hoʻi mai paha, ʻaʻole paha. No laila he wahi hōʻike wale ia i ka manaʻo o loko. He haliʻa ma kona ʻano. Haliʻa ka pilina mai mua mai paha, kahi manawa ma ke kaʻina manawa, kahi manawa ma ke kaʻina o ka ʻāina, kahi i launa hele ai. Inā ua lōʻihi nā makahiki, nui paha nā wahi i ʻalo pū ai i nā hana. He wahi pūʻulu manaʻo e haliʻa ana i ka pilina.

Puakea: It’s a type of mele –a chant– that shows love and a relationship to a person, usually someone who had passed on. Sometimes it can be done for a person who is leaving, knowing they may or may not come back. So, it’s an expression of what’s inside a person. It’s a fond recollection, in a sense. The relationship is recalled, sometimes in order of time, sometimes in order of places where the two people spent time together. If the relationship spanned many years then there might have been several places where things were done and experienced together. It’s a collection of thoughts that recalls a relationship.

H: Ma ke ʻano he māhele ia no ke kūmākena ʻana, i mea aha ke oli ʻana o ka poʻe i ke kanikau?

H: As a part of the grieving process, what is the function of chanting kanikau?

P: ʻO ka mea nui paha ka hoʻonā ʻana, ma kekahi ʻano. Ma ka hoʻokuʻu ʻana a ka hoʻokino ʻana i nā ʻano manaʻo o loko ma o ka huaʻōlelo a me ka leo paha, ma laila nō e hoʻomālie ʻia iho ka naʻau. Ma ke ʻano he hoʻohanohano no ka mea nona ke mele, he ʻano hōʻike, ma ke ākea, i kēlā ʻano manaʻo o kekahi. No ka mea, [ʻo ka] mea maʻamau ʻaʻole ʻoe kanikau iā ʻoe iho, ua pili i kekahi kanaka, eia naʻe ma laila [i loko ou] paha ka ʻanoʻano i kupu ai.

P: Possibly the most important thing is easing the pain, in a way. By releasing and giving form to the thoughts through words and maybe vocalization, that’s how one’s feelings are calmed and settled. As a honoring of the one for whom the mele was written, it is a display, in front of others, of those kinds of thoughts and feelings in someone. Normally you do not chant a kanikau to yourself; it is about another person, but the seed that gave rise to it was there [in you].

H: Ma kou naʻau ponoʻī?

H: In your own feelings?

P: ʻO ia nō. ʻAʻole wau i haku i kanikau no ka poʻe a pau i hala aku, eia naʻe aia kekahi a hoʻomanaʻo wau i ka noʻonoʻo nui ʻana. Ma laila i hoʻomaka ai ka hoʻonoho ʻia o ka manaʻo a ua ʻōʻili auaneʻi kekahi mele.

P: Yeah. I didn’t compose kanikau for all the people [I’ve known] who’ve passed, but I did for a few and I remember really thinking about it. And that’s when thoughts started to organize and then a mele emerged.

H: ʻOkoʻa kēlā, ʻokoʻa kou haku ʻana i nā ʻano mele ʻē aʻe?

H: Is that different than when you compose other kinds of songs?

P: Like paha kēlā ʻano ʻupu o ka manaʻo, kūpinaʻi kekahi mea i loko o ka noʻonoʻo, ma laila e hoʻomaka ai kekahi mea. ʻO kekahi poʻe i hala aku i ke ala hoʻi ʻole mai, noʻonoʻo nui ʻia, ʻaʻole naʻe ma kēlā ʻano like. ʻO kekahi wale nō, kahi e pono ai ka helu papa ʻana mai, a ʻano hoʻomanaʻo iaʻu iho a haʻi aku paha i ka lehulehu, penei nō māua. No ka mea pili mau ke kanikau i ka haku mele a i ka mea nona ke mele. ʻO ia paha kahi mea ʻano ʻokoʻa. I ka haku ʻana i ke mele maʻamau, aia nō ka hua ʻano pili iā ia iho. ʻO ke kanikau, he hōʻike i ka pilina o ka haku mele me ka mea nona ke mele.

P: Well, that thing of recurring thoughts is probably the same, something repeating itself in your mind, that’s where it starts. Some people who have passed I think about a lot, but not in that same way. Only for some of them do I feel the need to recount things in order and sort of remind myself, and maybe tell a wider audience: this is how we were. The kanikau is always about both the composer and the one composed for. That is maybe one of the differences. When you write a typical song, the product relates to itself. Kanikau, on the other hand, show the relationship of the composer to the person the song is for.

H: Ka hua i ka umauma o ka haku mele?

H: It’s the product of a message within the composer?

P: ʻO ia nō, a hoʻokomo ʻia. You know, ʻano hoʻohalahala wau i kekahi o ka poʻe haku mele inā hoʻokomo nui ʻia lākou i loko iho. Manaʻo wau, he mea kēlā e ʻano emi ai ke ʻano mau o kēia mele, ke ʻano laulā paha.

P: Right, and it is put in [the song]. You know, sometimes I sort of fault some composers if they insert a lot of themselves [into a song]. I think it can be something that diminishes the enduring nature of a composition, its broader accessibility.

H: ʻOkoʻa naʻe ke kanikau, he wahi kūpono e hōʻike ai iā ʻoe iho?

H: Kanikau are different though? An appropriate place to show oneself?

P: ʻAe. ʻAʻole paha kālele nui ʻia kēlā, eia naʻe, aia ʻoe i loko.

P: Yes. That probably isn’t highly emphasized, but you’re in there.

H: He mea kōkua paha ke kanikau ma ka hoʻokuʻu ʻana i ke kanaka i hala?

H: Do kanikau help us to release the person who has passed?

P: Manaʻolana wau ua noʻonoʻo ka poʻe he ʻano makana kēia no ka mea i hala, ʻeā, he wahi mea e hōʻolu iā ia iho, inā aia ʻo ia ma laila, eia au ke hōʻike nei i koʻu aloha. Kahi manawa, oli au ma ka hoʻolewa, inā ʻupu ka manaʻo, a hoʻohana wau i kekahi oli i maʻa iaʻu, a he mea ia e hōʻike pōkole i koʻu aloha, koʻu ʻano kūnewanewa i ke kaumaha, eia naʻe me ka manaʻolana..me ka hoʻokuʻu. Noʻu iho, he mea ʻano koʻikoʻi. Hoʻokuʻu ʻia. Pēlā ka lālani hope o ke mele, ‘E kuʻu hoa, e hele ʻoe, hele mālie ē.’ Me ka manaʻolana, i ka mālie o ka holo a me ka hoʻokuʻu, e holo nō. ʻO kēia kou wā e holo ai. He ʻano hopena kēlā o kekahi mau haʻawina i ʻike ʻia. He mea nui ka hoʻokuʻu.

E kuʻu hoa, e hele ʻoe, hele mālie ē.

P: I would hope people see it as a gift to the one who has passed, you know, a small thing to soothe them, and if they are present [in spirit], then ‘Here I am, showing you my love.’ Sometimes I will chant at funerals, if I feel moved to, and I use a chant that I know well, something short that shows my love, the reeling sadness I feel, but also, hopefully, the releasing of them. To me, that is something really important. Let them go. That is the last line of the song: ‘My friend, go, go peacefully.’ With hopes for a peaceful journey and release, go on. This is your time to go. That came out of some things I experienced. Letting go is important.

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

H: He aha ka mea e ʻokoʻa ai ke oli ʻana i ke kanikau me kekahi ʻano oli?

H: How does chanting a kanikau differ from presenting other chants?

P: Nui nā ʻano leo. Hiki ke hana ʻia ma ka hoʻuēuē, ma ke ʻano kāwele, ma nā ʻano like ʻole paha. Ma ke ʻano o ka leo e hoʻokino ʻia ai kēlā mau manaʻo a no laila ʻo ia paha ka mea a ka mea oli e noʻonoʻo ai. Hoʻomanaʻo ʻoe i ka noho ʻana o John Papa ʻĪʻī [ma ka hoʻolewa o Kamāmalu] a oli ʻo ia a ao ka pō. Noʻonoʻo au i ke ʻano leo ma loko o laila. ʻAʻole paha he hōʻuēʻuē o ʻuī ʻia paha ʻo ia.

P: There are many styles of vocalization. It can be done in a hoʻuēuē style, in a kāwele style, probably in most styles. The style of vocalization is what gives form to the thoughts therein, so that is probably what the chanter needs to think about. You remember [that story about] John Papa ʻĪʻī [at the funeral of Kamāmalu] and how he chanted all night long. I wonder what styles of vocalization he used then. It probably wasn’t all hoʻuēuē or he would have been completely wrung out.

H: ʻOkoʻa ke kanikau haku ʻia e ke aliʻi, ʻokoʻa ka mea haku ʻia e ka makaʻāinana?

H: Are kanikau written by the chiefly class different than those written by the common people?

P: ʻAʻole paha nui ka ʻokoʻa o nā mea e haku ana, ʻoiai aia nō i ka ʻike a me ka maʻamau. Eia naʻe, ʻokoʻa paha ka mea nona ke mele. Inā hana ʻia no kekahi aliʻi, ʻokoʻa paha ke ʻano ʻōlelo o loko, ʻokoʻa nā ʻano hoʻohanohano, kēlā ʻano mea. Eia naʻe, kahi nani o ka nohona Hawaiʻi, ʻo ia ka paʻa o ka ʻike ma nā pae like ʻole. He makaʻāinana paha ʻoe, akā mahalo ʻia kou ʻike. He aliʻi paha ʻoe, ʻaʻole naʻe kēlā he hōʻailona ua paʻa ka ʻike a pau iā ʻoe. ʻAʻole wau ʻike inā pēlā nō i ka wā kahiko loa, eia naʻe i ka wā “naʻauao” mahalo ʻia ka ʻike ma kona mau ʻano a pau, ka ʻike kuluma, ka ʻike Hawaiʻi, ka ʻike kahiko, a me ka ʻike hou.

P: The people composing them were probably not all that different, as it depended on what you knew and what was commonplace. However, the person being composed for was probably different. If it is done for a chief, the uses of language might be different, the ways of honoring them, that kind of thing. But one of the beautiful things about Hawaiian lifestyle norms was people having knowledge on all sorts of levels. You might be a common person, but I appreciate what you know. You might be a chief, but that is not a sign that you know everything. I don’t know if that’s how it was in pre-contact times, but in the era of “enlightenment,” knowledge was appreciated in all its forms; knowledge that was handed down, Hawaiian knowledge, old knowledge and new knowledge.

H: ʻO ke kūlana o ka ʻōlelo ma ke kanikau, he ʻano kiʻekiʻe paha i kou kuhi?

H: In terms of the level or register of language in kanikau, would you say it is fairly high?

P: ʻAno kiʻekiʻe, akā...ʻaʻole ʻimihia ke kiʻekiʻe loa, ʻeā, i kuʻu wahi manaʻo. I ka nui o nā kanikau aʻu i ʻike ai, kuhi ʻia nō nā mea ma ka lihi o ka nohona kanaka, ʻoiai he mea ia o ka ʻaʻe ʻana i kēlā lihi. No laila, ʻimihia nā mea ma ka laulā. ʻO ke kino o ke mele, ʻo ia nō nā mea o ke ola, no laila ʻano nui nā mea maʻamau, ʻapo koke ʻia, kēlā ʻano mea. No ka mea he poʻe noʻonoʻo, ʻeā, e haku ana i kēia ʻano mele. Noʻonoʻo lākou i kēlā lihi a ka mea hala e ʻaʻe ana, a noʻonoʻo wau ʻo ia paha kahi kumu e kuhi aku ai i kēlā ʻano māhele o ke ola. ʻAʻole kēlā ka māhele o ka nohona no kēlā lā, kēia lā.

P: You know, it’s kind of high, but...really high language is not what composers went after, in my opinion. In many of the kanikau I have seen, things on the periphery of human existence are indicated, since [death] is about going beyond that edge. So, what composers sought out was expansive language. In the body of the song were things about life, so lots of the normal stuff that’s quickly grasped, that kind of thing. You know, these were thoughtful people who wrote these songs. They contemplated that edge that the departed was crossing, and I think that’s one of the reasons to direct attention to that part of life. That isn’t the stuff of daily life.

What composers sought out was expansive language.

E like me kā Malo no Kaʻahumanu [ʻike ʻia kēlā ʻōlelo ʻo] Mihalanaau. Hoʻokomo ʻia kekahi mau huaʻōlelo maʻa ʻole [i ka poʻe], mea kakaʻikahi, a kahi manawa haku ʻia nā huaʻōlelo ma ka hoʻohui ʻana, i mea e ʻapo ai, i mea e hoʻākāka ai kēlā ʻano mea ma ka lihi o ke ao. Inā e kuhi wale ana i ke kahe ʻana o ka wai i loko o ke kahawai, maʻa ihola i nā huaʻōlelo e pono ai. Inā e noʻonoʻo ana ʻoe i ke kahe ʻana o kēlā wailua, ma laila ka noʻonoʻo, ma laila ka ʻōlelo.

Like Malo’s [kanikau] for Kaʻahumanu [where we see that term] Mihalanaau. Words are put in that people are not used to, that might be rare, and are sometimes invented by joining words, in order for people to grasp [concepts], or to clarify those things on the edge of existence. If you are just going to talk about wai (water) flowing in a river, then you already know the words to use. If you are thinking about the flowing of the wailua (spirit), then you contemplate that and talk about it.

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

H: No laila, kekahi o nā huaʻōlelo, ʻaʻole paha he kūlana kiʻekiʻe loa, akā koho pono ʻia, wae ʻia.

H: So some of the words might not be super advanced or fancy, but they are well chosen, carefully selected?

P: ʻAe. Kekahi manawa, haku ʻia! Eia naʻe, ʻaʻole kēlā ke kino o ke kanikau. He mea e hoʻohanohano a hoʻokiʻekiʻe i ke kūlana, ʻaʻole naʻe kēlā ke ʻano o ka ʻōlelo mai luna a lalo.

P: Yeah. Sometimes they are made up! However, that is not the bulk of the kanikau. It is something to bring honor and elevate the person, but that is not the kind of language throughout.

H: He mau haʻawaina nui paha ma loko o nā kanikau, ʻaʻole e loaʻa ana ma nā ʻano mele ʻē ʻae?

H: Are there big lessons or kinds of knowledge in kanikau that we can’t get from other kinds of mele?

P: Nui nā mea e loaʻa ana ma nā mele like ʻole. Ua paʻakikī ka ʻōlelo ʻana aia kekahi mea ma neʻi i ʻike ʻole ʻia ma kahi ʻē. Eia naʻe, ʻano kaukaʻi ʻia nā kanikau no ka hōʻike ʻana, hoʻokino ʻana i nā pilina o nā kānaka. Inā makemake e hoʻomapopo i ka moʻolelo o kekahi, pono e nānā i nā kanikau a e kuhi koke ana: ʻO wai ka poʻe i pili, ma hea i pili ai, he aha ke ʻano o ka pilina? Kēlā ʻano mea. No laila he hune ʻike ko loko a he koʻikoʻi kēlā, he waiwai kēlā, no ka moʻokūʻauhau, no ka moʻolelo, no ka hoʻomaopopo ʻana.

P: Lots of things can be found in all types of mele. It’s hard to say that there’s something here that can’t be found elsewhere. However, kanikau are kind of relied upon for showing and giving real form to the relationships of people. If I want to understand someone’s story, I have to look at kanikau composed for them, because these will indicate: Who were the people close to them? Where did they become close? What was their relationship like? Those sorts of things. So there’s bits of knowledge in them and that’s really important and valuable, for genealogy, history and general understanding.

ʻO kahi mea ma laila, noʻonoʻo au, he mea [ke kanikau] e hoʻokino ana, e hoʻākāka ana i ke ʻano o ka nohona a me ka ʻikena o ka poʻe o ia wā. ʻAʻole ʻo ka poʻe a pau, ʻo ka poʻe i loko o kēlā pōʻai. Kuhi ʻia ke ʻano o ka huakaʻi ʻana, ke ʻano o ka pilina, ke ʻano o ka ʻai ʻana, ke ʻano o ka ʻalo ʻana i nā hihia, nā pilikia, kēlā ʻano mea. He ʻano puka komo kēlā i loko o ka nohona o ia wā. Ma muli o ko kāua nānā iho i kēlā mea a Malo, noʻonoʻo au i kēlā pilina o Malo lāua me Kaʻahumanu, ma ke ʻano he kaikuahine. ʻAʻole he hoahānau maoli, ʻaʻole he hoahānau ponoʻī, he hoa hānau ma muli o [ka ʻekalesia]. Ma muli o kēia komo pū ʻana ma ka ʻekalesia, hiki iaʻu ke kapa aku iā ʻoe he kaikuahine, he hoahānau, ʻeā, eia naʻe, he mea kiʻekiʻe ʻoe, he mea haʻahaʻa wau.

Another thing to mention in that vein, I think, is that kanikau give shape to and insight about the lifestyle and the perspectives of people of that time. Not everyone, but the people in that [person’s] circle. Different thing are shown, like how they traveled, what the relationship was like, how they ate, how they faced problems and challenges, those kinds of things. It’s a sort of window into the existence of that time. Because we just looked at that kanikau by Malo, I think about the relationship of Malo and Kaʻahumanu, her being a “sister” to him. Not a real or blood relative, but a relative through the church. ‘Because we both joined the church, I can call you my sister, my relative, but you are of high status and I am not.’

Kanikau give shape to and insight about the lifestyle and the perspectives of people of that time.

H: ʻO ka hōʻike ʻana i ke kaumaha lua o ka naʻau, he mea pili loa paha i ke kanikau a i ʻole ʻike ʻia kēlā ʻano mea ma nā mele aloha kekahi?

H: Expressing deep sadness, is that something quite specific to kanikau or is it seen in love songs too?

P: Ma kekahi ʻano, ʻike ʻia nā ʻano a pau o kānaka ma nā mele, ʻeā? Eia naʻe, ka ʻokoʻa o ke kanikau, noʻonoʻo au, ʻo ke kaumaha, kēlā ʻano ʻoki ʻana i ka pilina, no ka hala ʻana, no ka haʻalele ʻana, no kekahi mea, ʻo ia kekahi mea ʻike ʻole ʻia ma ka nui o nā mele ʻē aʻe. ʻO kekahi mea, ma nā mele aloha, nā mele inoa, nā mele pai aliʻi, nā ʻano mele ʻē aʻe, ʻo ke kumuhana ka mea nona ke mele. Inā hoʻohanohano ʻoe iā Wailau, ʻo Wailau nō ka ʻōnohi, ʻeā. Akā ma ke kanikau ʻo ka pilina kekahi mea koʻikoʻi, ʻaʻole ʻike mau ʻia, ua kamaʻilio iki kāua, akā he māhele e ʻike ai ʻoe he kanikau kēlā.

P: In a way, everything about human nature is seen in mele, right? However, the difference with kanikau, I think, in terms of sadness, is that ending of a relationship because someone has passed away or left, or for another reason, that is something that isn’t seen in the same way in other types of mele. Another thing is that in love songs, name songs, songs to honor chiefs, and other types of songs, the main subject of the song is the person who it is composed for. If I am honoring Waiau, Waiau is the center [of the song]. However, with kanikau, the relationship is the thing of real import. We talked a bit about that, but it’s one of the ways you know it’s a kanikau.

H: Pehea ka loli ʻana o ke kanikau i ke au ʻana o ka manawa?

H: How have kanikau changed over time?

P: ʻO ke kanikau mua loa i ʻike ʻia ma nā nūpepa, ʻano pōniuniu ka noʻonoʻo i ka hoʻomapopo ʻana mai i nā ʻano aka. ʻOiai ma nā mele a pau, ʻike ʻia ka manaʻo ma o ke aka. ʻO nā aka nā mea i akāka paha i ka poʻe o ia wā. E like me kā kākou haku ʻana i nā aka o kēia manawa. ʻO nā mea e akāka ana iā kākou, e huikau ana ʻelua hanauna aʻe nei. No laila, haku au i kahi mele a hoʻokomo au i nā aka i pā ai kou naʻau kekahi. Pono ka mea hoʻolohe e hoʻomaopopo, e ʻano koni kēlā manaʻo i loko. E loli ana ke ʻano mea e koni ai ka puʻuwai.

Pono ka mea hoʻolohe e hoʻomaopopo, e ʻano koni kēlā manaʻo i loko.

P: The first kanikau seen in the [Hawaiian-language] newspapers, the mind sort of dizzies when attempting to understand the metaphors in it. In all mele, ideas or thoughts are seen through metaphor. Metaphors are things that are probably clear to the people of the time. Just like how we create metaphors today. Things that are clear to us will be confusing to those two generations from now. So, I write a song and I put things in it that will touch you, too. The person hearing it needs to understand and sort of feel the pang of the meaning inside. The kinds of things that touch the heart are changing [over time].

H: No laila noʻonoʻo ʻia ka naʻau, ka puʻuwai paha o haʻi kekahi?

H: So the heart and feelings of others are also considered?

P: ʻO ia nō, ʻo ia nō. Inā huikau a pohihihi ka mea holoʻokoʻa ʻaʻole ia he hōʻike. ʻAʻole ia he makana ma kēlā ʻano.

P: Yes. That’s it. If the whole thing is confusing and mysterious, it isn’t insightful. It isn’t really a gift, in that sense.

H: ʻOia. ʻAʻole e ʻapo ʻia a hiʻi ʻia e like paha me ka manaʻo o ka mea haku.

H: Right. It isn’t going to be understood and treasured like the composer might hope.

P: ʻAe. ʻOia lā. Oia lā. Kohu like me ka makana. Inā hāʻawi au iā ʻoe i kahi makana a wahī ʻia me ka pepa maikaʻi, me ka hīpuʻu o luna a mea lā, ʻaʻole naʻe wau ʻae iā ʻoe e wehe a ʻike ʻia mai waho mai wale nō, he aha lā ia? ʻAno emi iho ka waiwai o kēlā makana, a kau wale ana me ka maopopo ʻole iho. A nānā, he aka kēlā i hiki ke ʻaʻapo koke. Inā kamaʻilio ʻoe iā Kalaniʻōpuʻu pili i ka makana i wahī ʻia me ka hīpuʻu, e kūnānā wale ana iā ʻoe me ka noʻonoʻo, "Ahhhhh shua." Pēlā paha i loli ai ke au o ka manawa.

P: Yes. Exactly. It’s like a present. If I give you a present and it’s wrapped up in nice paper with a bow on top and all that, but I don’t let you open it and it’s only viewed from outside, then what is it, really? The value of that present is kind of diminished and it just sits there, with no understanding of what it is. And look at that - that in itself is a metaphor that’s easy to get. If you talk to Kalaniʻōpuʻu about a present wrapped up with a bow, he’s just gonna stand there and stare at you like, “Ummmm, sure.” So that’s maybe how things changed over time.

H: I ka laha ʻana mai o nā nūpepa, ua loli paha ke ʻano o ka haku kanikau ʻana, ʻoiai e ʻike ʻia ana nā mele e nā kānaka like ʻole mai ʻō a ʻō o ka paeʻāina? Ua hele paha a laha kekahi mau aka ma muli o ia kūlana?

H: With the spread of newspapers, was there a change in how kanikau were composed, since mele were being experienced by all sorts of people across the island chain? Are there metaphors that became somewhat common because of this?

P: Ma ka hoʻolaha, ma ka lohe ʻia, kāu mea e mahalo ai, ʻo ia kāu e hoʻopili ai. No lail, noʻonoʻo wau, ʻo ke kākau ʻana iho i nā mele, he mea nui kēlā ma ka hoʻolaha ʻana i kekahi mau ʻano i mahalo ʻia, a ulu auaneʻi, a pēlā e manamana aku ai nā ʻano mea. Pēlā e hoʻopili ʻia ai. A ma ka haku mele ʻana, mahalo ʻia kēlā ʻano mea he “kuhi.” Inā huki wau i kekahi lālani, kahi hopuna ʻōlelo, māmala ʻōlelo, mai ke mele no Hiʻiaka a hoʻokomo i loko o kaʻu mele, inā maopopo iā ʻoe kēlā moʻolelo o Hiʻiaka, he ʻano puka komo kēlā, kahi e noʻonoʻo ai, ma mua o ka neʻe ʻana aku i ka lālani hou. Kohu like me ka pūnaewele. Inā aia kahi link, a hele ʻoe i kēlā link, ʻoi aʻe paha ka waiwai o kāu e nānā nei. Inā ʻaʻole ʻoe hele i laila, lawa ka nani ma kēia ʻaoʻao. Pēlā ma ke mele. Inā maopopo iā ʻoe kēlā moʻolelo o Hiʻiaka, ʻoi aʻe paha ka ʻono o kāu mele, inā naʻe ʻaʻole maopopo iā ʻoe, lawa ka ʻono ma ʻaneʻi. Inā kuhi wau iā ʻoe he pua loke no Maui, he ʻano pili kēlā aka i nā ʻano wahi ʻē aʻe i mahalo ʻia ai ka loke o Maui.

P: In print and in hearing things, what you appreciate, that is what you emulate. So, I think that mele being written down is a big part of the spreading of things that were admired, and then it grew, and that’s how things proliferate. That’s how they are repeated or copied. Also, in composition, “kuhi” or “nods” (references) to other things are appreciated. If I take a line from a song for Hiʻiaka, that is kind of a point of entry to think about [that song] before moving on to the next line. It’s like the internet. If there’s a link and you go to that link, then the value of what you are looking at might increase, but if you don’t go there, it’s beautiful enough on this side. Mele are the same. If you know that story of Hiʻiaka, then your song probably has more flavor, but if you don’t, it’s plenty delicious right here. If I refer to you as a rose from Maui, that sort of connects to all the other places that roses of Maui have been appreciated.

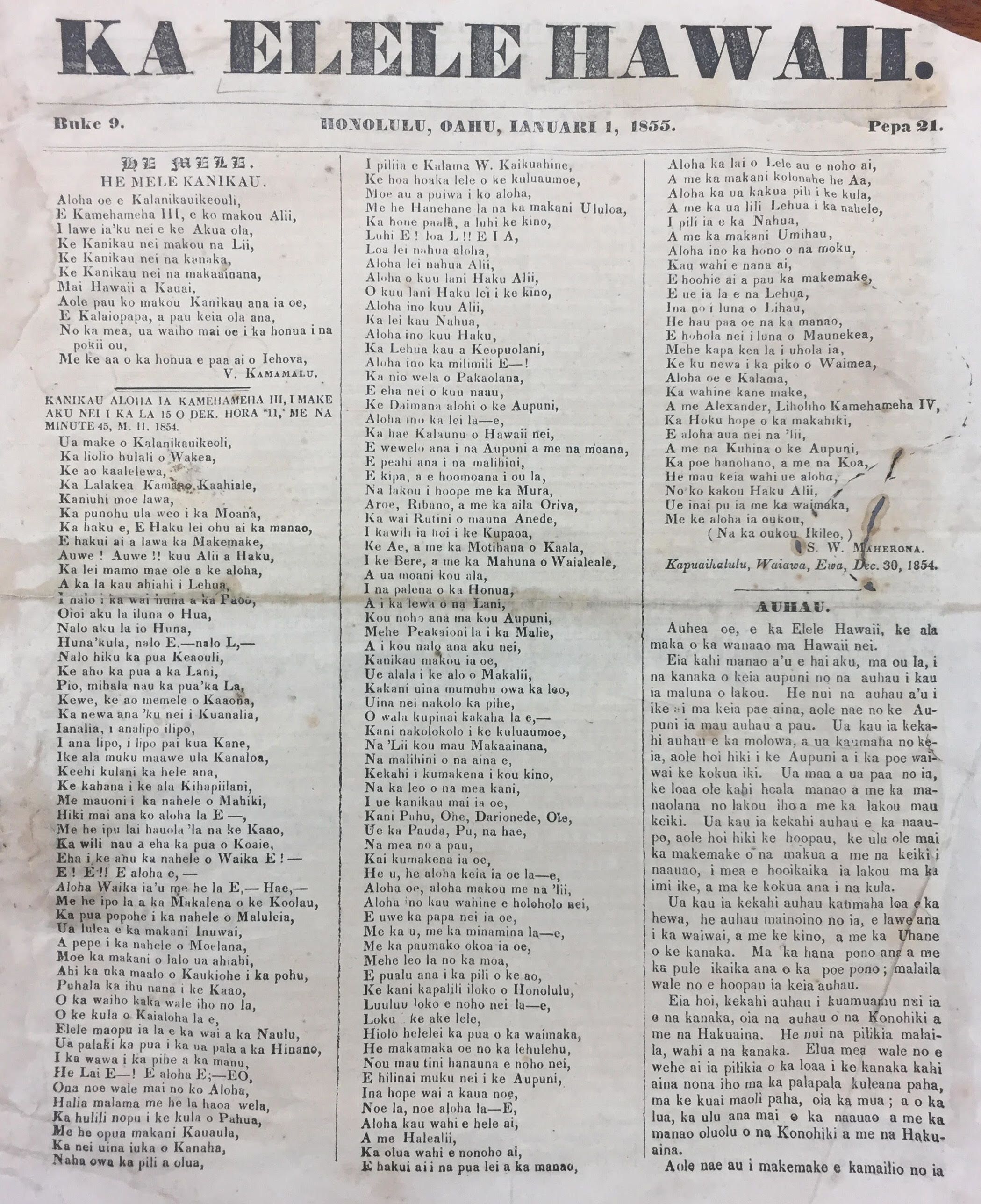

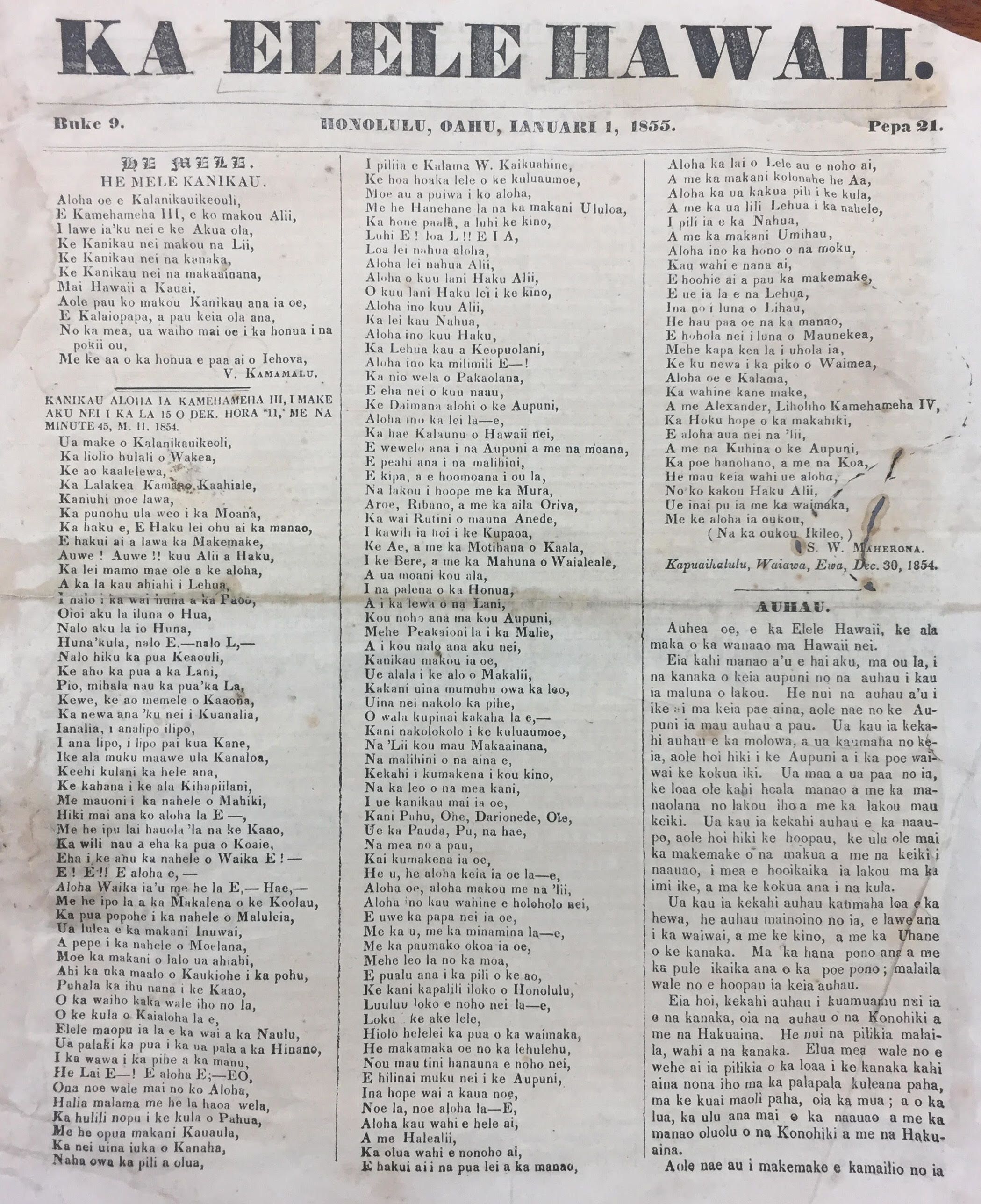

ʻO ka nūpepa ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi ʻo Ka Elele Hawaii

The literacy of the populace and the spread of that literacy, those two work together, the dynamic there is so powerful, it shaped a nation, and not just as a political entity, but as a cultural and social [one]. I mean, suddenly Kauaʻi aka (metaphor) are being incorporated in Kaʻū mele. The beauty of it [the exposure] is that it enhanced and added and built. So, a farmer in Waiau is exposed to royal poetry from Kona in a way that never would have happened. Look at what the available literature and literacy was. [Before the newspapers] only a chief would have been exposed to half of those things, but now the fisherman in Waiʻanae is seeing it as well. There was a broad level of exposure for a broad base of people.

There was a broad level of exposure for a broad base of people.

H: No nā kānaka o kēia au e makemake ana e haku i kanikau, he mau ʻōlelo aʻo paha kāu iā lākou?

H: For people today that are wanting to compose a kanikau, what’s your advice to them?

P: E nānā aku i nā laʻana he nui loa e kū mai nei. He mau ʻano loina o ka hoʻolauna ʻana, o ka hoʻokino ʻana i nā manaʻo, me ka panina. Aia nō ia mau mea i loko o ke kanikau. Mai lele wale a hana. Nui koʻu mahalo i ka mele Kepanī, ʻaʻole naʻe wau i ʻōlelo i ka ʻōlelo Kepanī no laila ʻaʻole wau hoʻomaka ma kēlā keʻehina o luna loa, ʻeā. E hoʻomaʻamaʻa i kāu ʻōlelo iho, e hoʻokamaʻāina i nā ʻano mele, nā loina mele a laila ʻoe e hoʻonohonoho ai. Inā ʻaʻole, then just write a love letter. Kekahi mea e noʻonoʻo ai, ʻaʻole kēia ka moʻolelo pilikino o ka mea i hala, ʻaʻole kēlā ke kumu o ke kanikau. He ʻokoʻa ka moʻolelo pilikino, he ʻokoʻa nā mele aloha, a pēlā ka moʻokūʻauhau. ʻAʻole kēia ka moʻokūʻauhau, ʻo kēia ke kanikau, no laila e makaʻala i kēlā māhele. ʻO ke kumu o ke kanikau kou pilina [i ke kanaka], no laila ʻo ia kekahi mea e makaʻala ai. ʻO ia paha ke kaona. No ka mea kuhihewa ʻia i kēia mau lā, ʻo ia ka hoʻohana ʻana i nā huaʻōlelo me ʻelua, ʻekolu manaʻo. Akā, ʻo ke kaona ka ʻanoʻano i kupu ai ka manaʻo e haku mele. ʻO kēlā ʻanoʻano ka mea e kuhi ana i nā ʻano aka, e wae ana i kekahi o nā huaʻōlelo, ʻaʻole naʻe kēlā kaona i loko o laila.

P: Look at the plethora of examples that there are. There are norms about how to open, form your thoughts into images, and close. Those things are in kanikau. Don’t just rush into it. Practice your own language, acquaint yourself with the different sorts of mele and composition practices, then start your own. If not, then just write a love letter. Another thing to consider is that it’s not the biography of the person who died, that is not the basis for a kanikau. Biographies are different, as are love songs and genealogy. This is not genealogy, this is kanikau, so we have to be alert to that. The basis for a kanikau is your relationship [to a person], so that is something to really watch. Maybe that is the kaona. These days kaona is erroneously assumed to be the use of a word in two or three ways, but kaona is actually the seed from which springs the impetus to compose. That seed will indicate the sorts of metaphors [you might use] and help you to select some of the words, but the kaona is not in the song itself.

Transcribed and translated by Hina Kneubuhl.

Mahalo

Visit the website of Awaiaulu to learn more about this organization.

A huge thanks to Jake Marote for his photographs. See his work on Instagram @jake_of_all_trades and on his website.

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

Kiʻi: Hina Kneubuhl

Kiʻi: Hina Kneubuhl

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

Kiʻi: Jake Marote

ʻO ka nūpepa ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi ʻo Ka Elele Hawaii

ʻO ka nūpepa ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi ʻo Ka Elele Hawaii