From Birth To Kanu

An interview with Camille Kalama of Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation

All parents want a solid foundation for their newborn child, a positive and protected beginning to their life outside the womb.

For many Hawaiians, this means careful handling of the child’s ʻiewe (placenta and afterbirth) from the moment of birth till it is put into the earth, along with the prayers and hopes of the parents. It makes absolute sense from a cultural perspective, yet the right to take a child’s ʻiewe home from the hospital has not always been respected or protected. In fact, a lot has happened in order for this right to be enshrined in law and safeguarded indefinitely.

In 2005, two couples went to Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC) for help because hospitals were refusing to give them their child’s ʻiewe after the Department of Health’s decision that year to classify placentas as “infectious waste.” The belief of many Native Hawaiians is the complete opposite. The ‘iewe that sustains a child’s life in the womb is treated with respect and appreciation after the child has been born, as it is still linked to the child’s wellness and survival. “That’s the fundamental difference,” says NHLC staff attorney Camille Kalama, “Hospitals look at it like baby and waste. Biohazard. For us, we don’t separate them. This is not baby and biohazard. They are born together. They are cared for differently, but we care for both of them.”

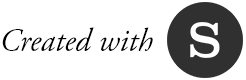

Camille Kalama in the ʻiewe design done by Kealopiko for the 2018 Makamaka Collaboration with NHLC.

Camille Kalama in the ʻiewe design done by Kealopiko for the 2018 Makamaka Collaboration with NHLC.

"This is not baby and biohazard."

- Camille Kalama

With NHLC's help, these two families took legal action. Ultimately, they did not receive a court ruling, because they were able to regain possession of their ʻiewe before the court process was completed. Thankfully, though, their legal battles induced change. Community uproar, organization, and action resulted in the creation and passage of a law in 2006 that guarantees parents in Hawaiʻi the right to take their child’s ʻiewe home with them from the hospital.

Kalama’s understanding of the importance of ʻiewe runs deep, along with her sensitivity and attentiveness towards her clients. These qualities must have brought great relief to the Native Hawaiian family who sought the help of NHLC a few years after these initial cases. The hospital where they had recently given birth had accidentally ‘disposed’ of their child’s ʻiewe (placenta). The couple had filled out the paperwork and gone through all the hospital’s required steps, only to be devastated by the news that it had been mistakenly incinerated. Human error had robbed them of this deeply personal part of their child’s birth. Kalama recalled the shock she felt, “I can’t imagine being in that situation and how awful that would feel.” As a mother who gave birth to two children at home, it was easy for her to mālama (care for and properly handle) her children’s ʻiewe. Knowing that homebirth is not an option for everyone, she was struck by this couple’s situation and immediately felt compelled to help. “This can’t happen,” she thought, “this family shouldn’t have to go through this.”

The number of other couples who have silently suffered the loss of ʻiewe in hospitals is unknown.

Although the law is a victory for Native Hawaiians from a cultural standpoint, it cannot guarantee success. That’s the heartbreaking truth Kalama wrestled with when she sat down with that first couple whose ʻiewe had been mistakenly destroyed. So much had happened just to secure the right, yet it wasn’t enough to prevent this kind of terrible loss. Camille says the couple felt blindsided, “They thought, ‘I did all my paperwork. I went through all the steps. I didn’t know I still had to worry about it.’” Since the 2006 law, a handful of families have come forward seeking resolution for the loss of ʻiewe, but the number of other couples who have silently suffered the same thing is unknown. Kalama’s huge capacity for aloha helps her clients as they navigate the legal system during this time of loss, “You can’t fully fix this for the family,” she says, “It’s such a huge blow at such a vulnerable time.”

"It's such a huge blow at such a vulnerable time."

- Camille Kalama

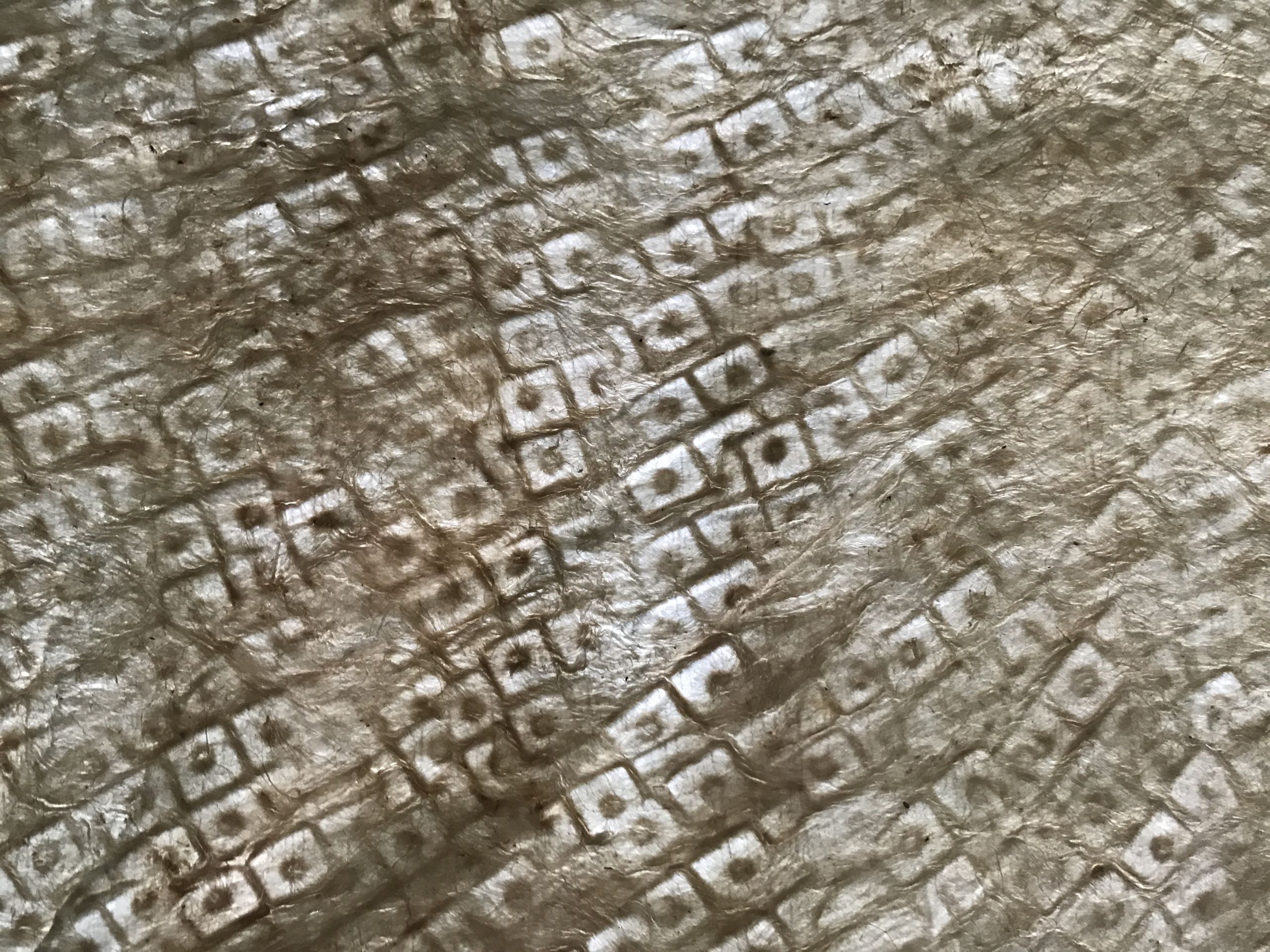

Mele Kalama-Kingma wearing the ʻiewe design.

Mele Kalama-Kingma wearing the ʻiewe design.

So what is the next step for parents in this situation? Mediation is often used, which means sitting down with the family and hospital staff to discuss what has happened. Kalama says this can be tricky. Hospitals may apologize for the family’s loss - cry with them even - but fear of liability often keeps medical organizations from formally acknowledging that they have done wrong. On top of that, they want the parents to keep quiet about what has happened. “This whole system that is trying to limit exposure and keep the families quiet is really like another form of trauma for them,” says Kalama. “It’s really hard for them to get resolution and to help other families in the future to avoid a similar situation.” Kalama also said that what’s really needed is a change of culture inside the hospitals so that all care providers understand the importance of handling ʻiewe with respect and care.

This whole system that is trying to limit exposure and keep the families quiet is really like another form of trauma for them.

If mediation doesn’t bring about resolution, couples can take their case to a medical claims panel. This panel determines whether or not a person has suffered emotional injury, how much it has affected their life and the amount of money they should receive as compensation for those damages. But how does one even begin to quantify such a thing? Kalama makes the point that for some Hawaiians, the process might feel strange or go against certain values they hold. For many, ʻiewe are irreplaceable.

For the families that NHLC has helped, their biggest hope is that expectant couples will avoid all of this. Kalama says that when these families find out another family has suffered the same loss in the same way, they relive the pain of their experience and think, “Is there more we could have done to prevent it? Or more we can do to get the message out to our people?” Kalama believes that by sharing knowledge and experiences, others don’t have to go through these kinds of traumas. “The best we can do is share our mistakes and our successes with the next generation.”

"The best we can do is share our mistakes and our successes with the next generation."

- Camille Kalama

How do expecting couples ensure the safety of their child’s ʻiewe? “It starts with being aware. Talking about it well before baby comes. Having it on our radar,” says Kalama. She adds, “Just because there is a process, we can’t rely on others - hospitals, doctors, nurses - who do not share the same values that we do to mālama the same as we will.” To assume full kuleana (responsibility) for the ʻiewe means having a plan for exactly what is going to happen at the birth. If you are giving birth in hospital, come prepared with a labeled container that fully seals and a cooler full of ice. Have a designated person on call, who you have fully briefed with instructions, to take it home straight away. If you are unable, for any reason, to do these things, insist that the ʻiewe be immediately stored in the freezer rather than refrigerated.

Kalama is supportive of the idea that parents or a family member should take the ʻiewe as soon as possible. And if the hospital says you cannot take it immediately? Be persistent and ask to speak to a supervisor. Kalama feels strongly that we need to fight for the right to mālama ʻiewe from birth until we can kanu (bury or plant it) and that we need to change our mindset and question the system when we are told we cannot do something that, at one point in our history, was so commonplace and accepted.

Kalama says that because ʻiewe are sacred and connected to our children, we have a duty to ensure that they are cared for and safeguarded until they are returned to the earth in an appropriate manner. NHLC is still working to find resolution for some of the families who are not able to kanu their child’s ʻiewe. Kalama is hopeful for them and grateful to those that are willing and able to share their story with others. To mālama ʻiewe makes sense to her on every level, “It’s a part of us, a part of our keiki, and part of their future. We re-connect our keiki to the ‘āina when we kanu their ‘iewe. In doing so, we give life to both."

Click here to visit the NHLC website and learn about their work.

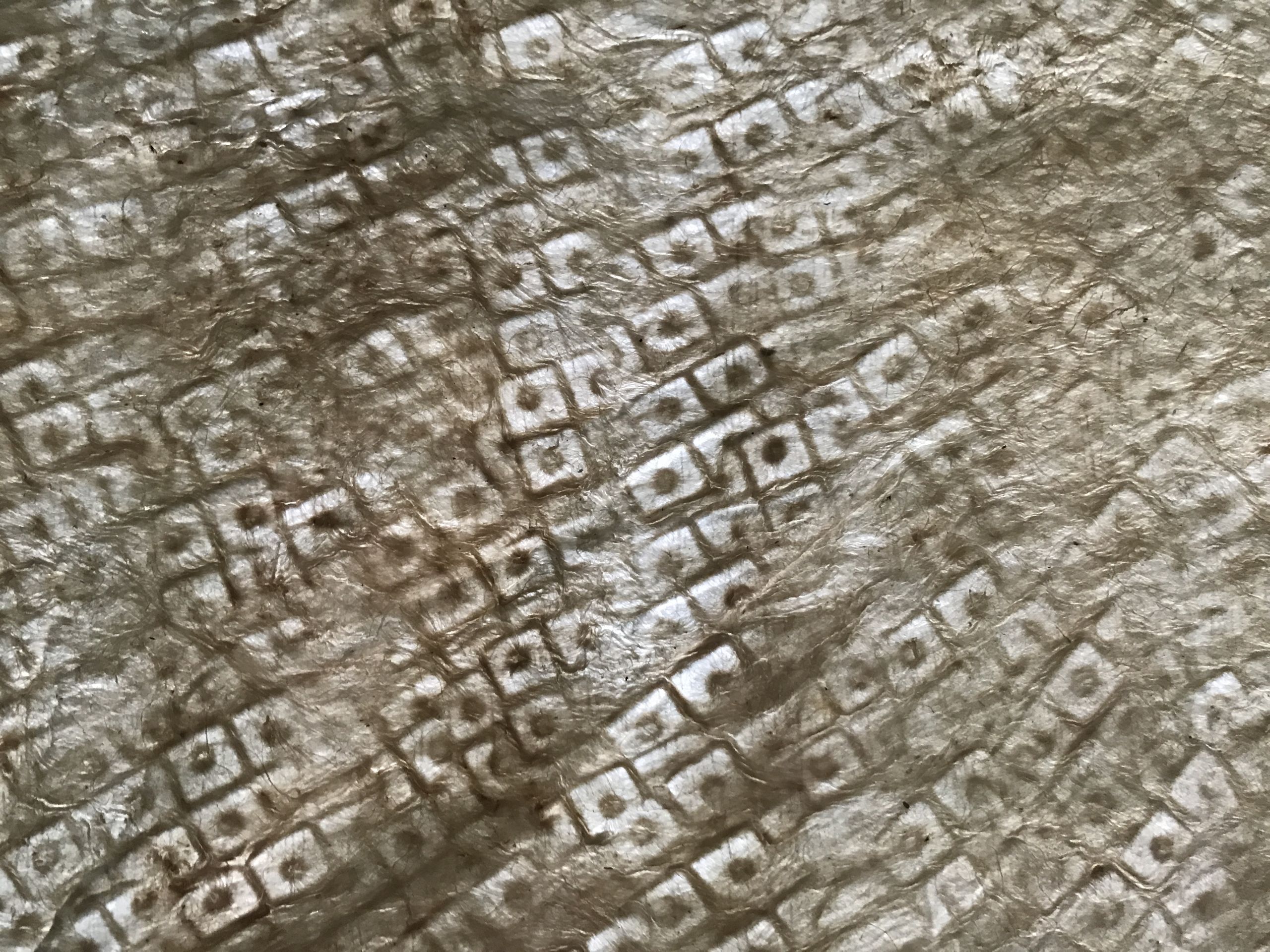

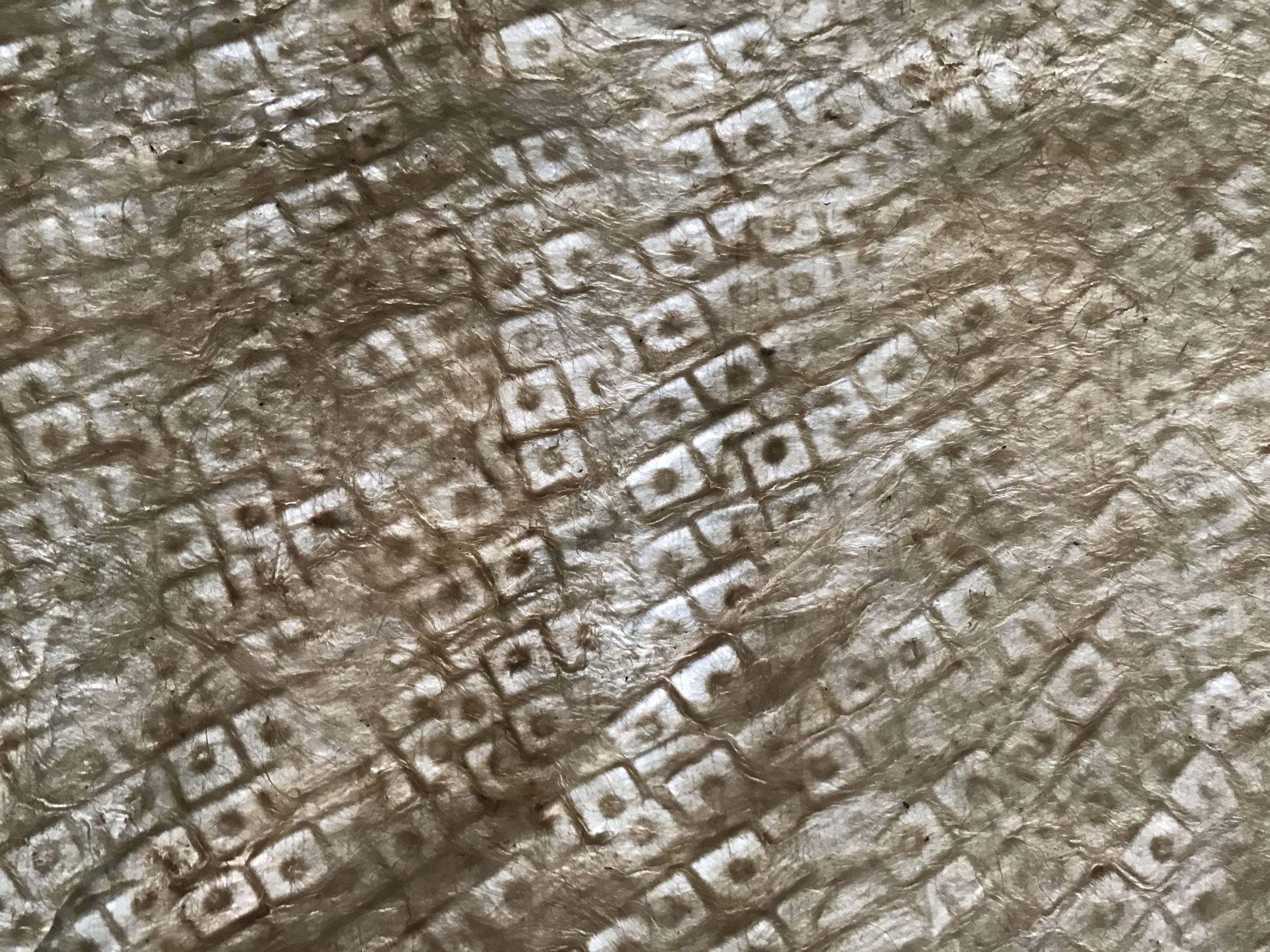

Sisters Mele Kalama-Kingma and Camille Kalama wearing ʻiewe pareu.

Sisters Mele Kalama-Kingma and Camille Kalama wearing ʻiewe pareu.

M A H A L O

Mahalo to Charlotte Armstrong, Shannon Wianecki, and Blaine Namahana Tolentino for advice on words

Images: Hina Kneubuhl & Jamie Makasobe

Models: Camille Kalama & Mele Kalama-Kingma

A huge Mahalo to Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, our Makamaka collaborators for 2018.

Click here to visit the Kealopiko website.