Lapa

Kapa design aesthetic

tucked deep into the folds

of time and space

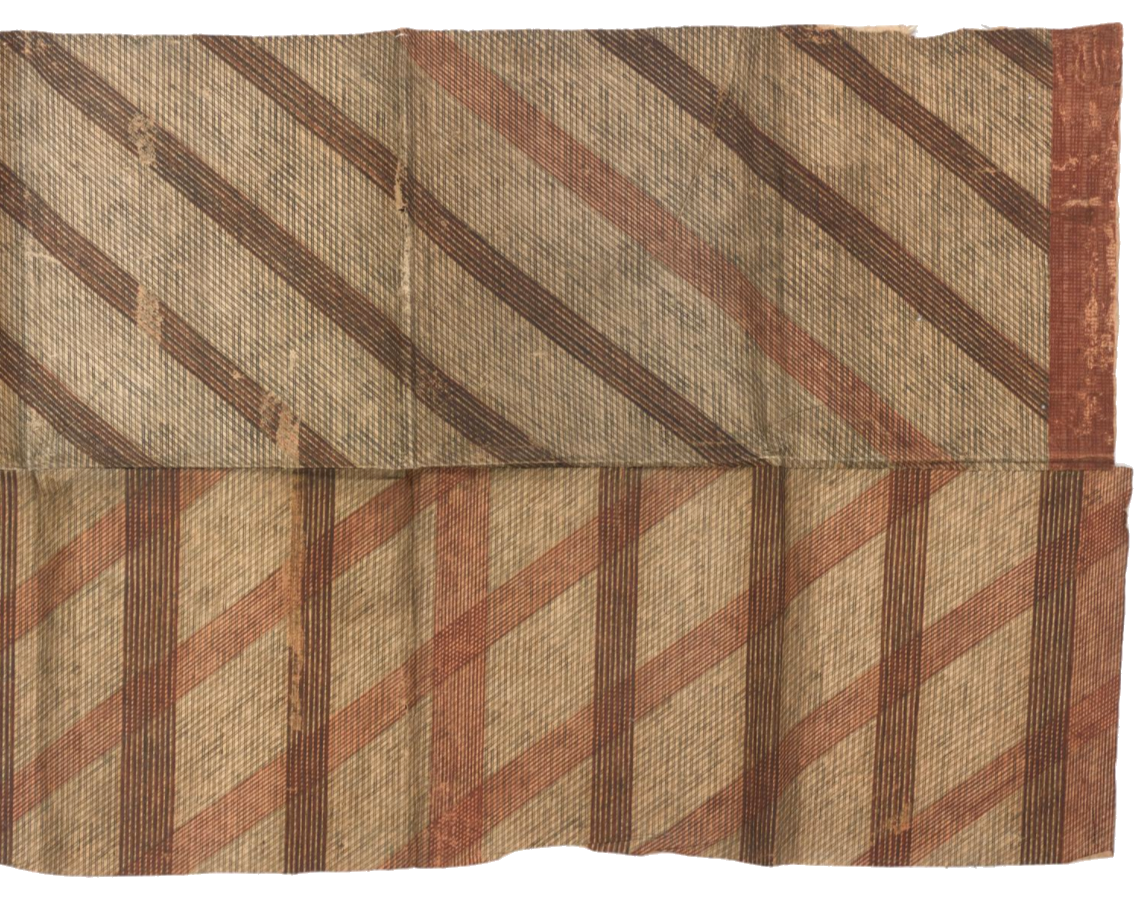

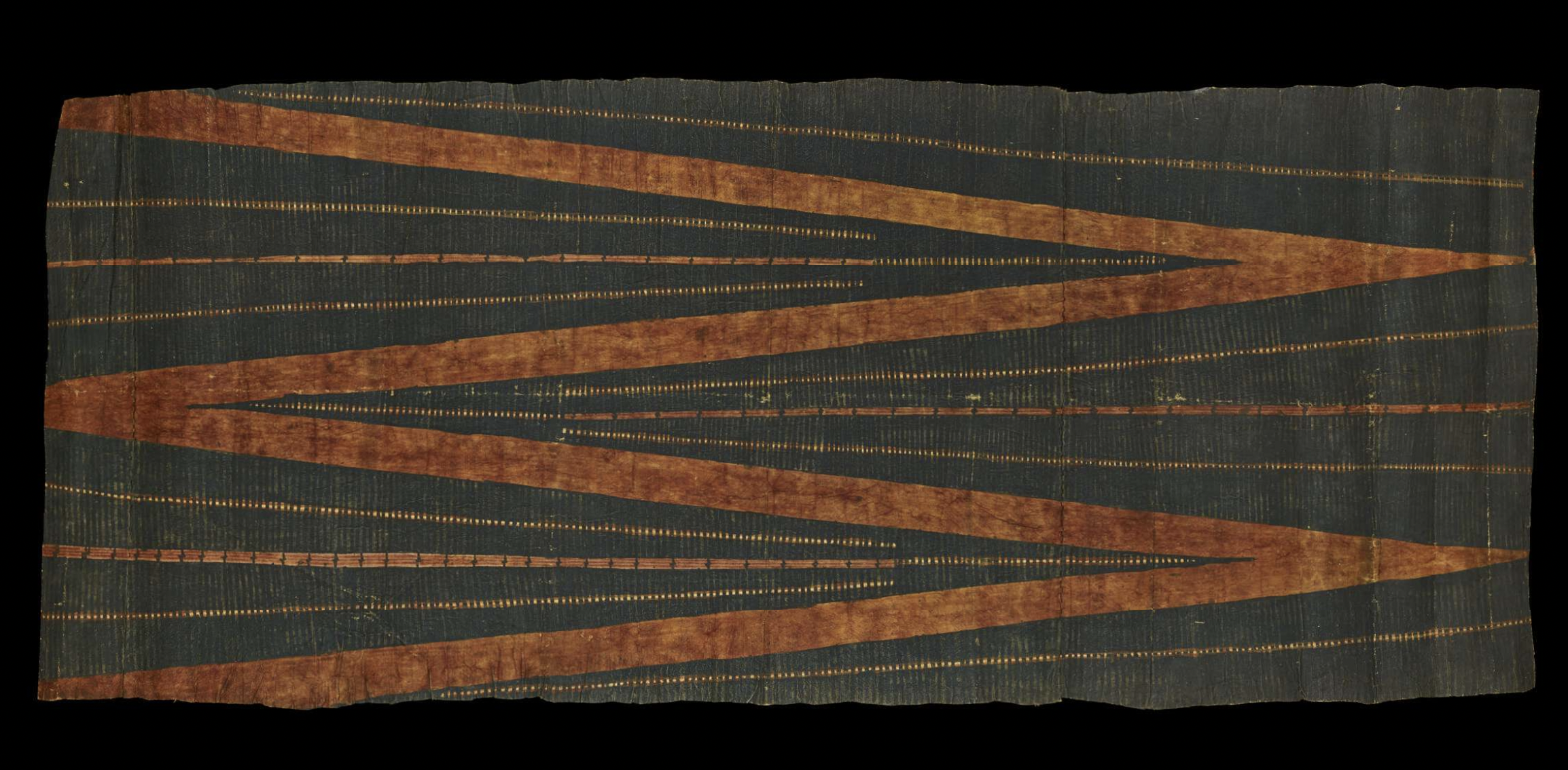

Although it is one of the oldest known techniques for surface decoration of kapa, lapa has somehow largely slipped from our grasp of Hawaiian aesthetics and our collective understanding of kupuna cloth.

ʻOhe kāpala has taken center stage and is what people see in their minds when they think of kapa design. The fine patterns and delicate beauty cannot be faulted, but in the flow of history, ʻohe kāpala is the kaikaina (younger sibling).

Lapa, the kuaʻana (older sibling), deserves its due as one of the oldest known forms of Hawaiian design and, arguably, one of the most stunning.

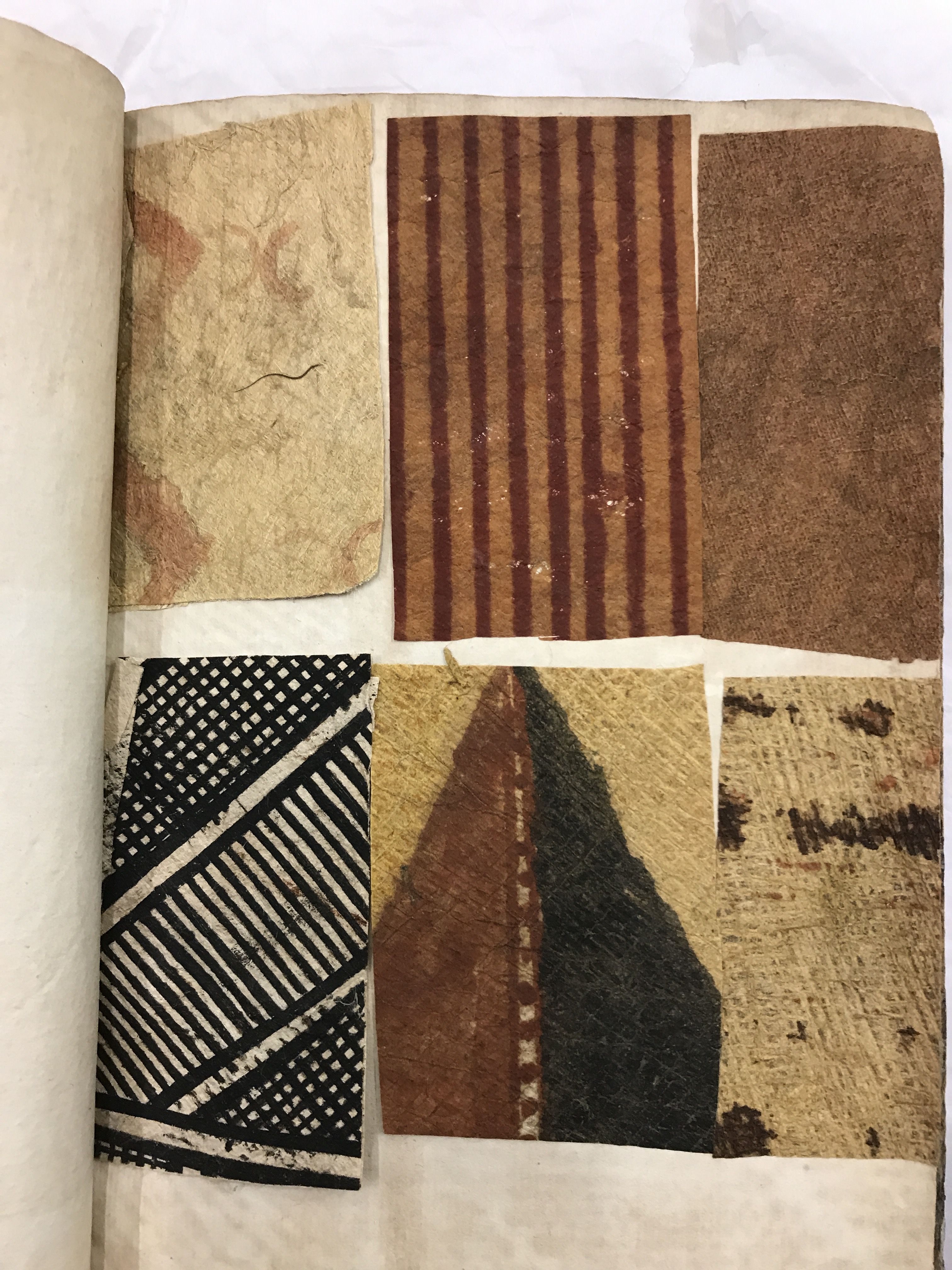

Below are some of the best surviving examples of this style of decoration.

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Lapa

the dancing of flames that warm the womb, lighting the fires of procreation

2. a. To spread or blaze, as fire or volcanic eruption; to excite or flare, as with passion; to animate...

Lapa

the door between worlds that shields the developing spark of life in the ipu ʻaumakua

4. n. Orifice of the womb.

Lapa

the flash of lightning that provides an immediate infusion of divine productive energy

Lapa

the lightning forks that harness creative currents, the original instruments for decorating kapa, the first fabric of life...

3. n. Bamboo liners, for tapa printing.

Kaʻa ka honua i ke kapa

a ka wahine

The world turns

on the fabric made by the woman

- Pule Hoʻīnana Kanaka, Haʻinakolo,

Ka Nai Aupuni, 29 April 1908

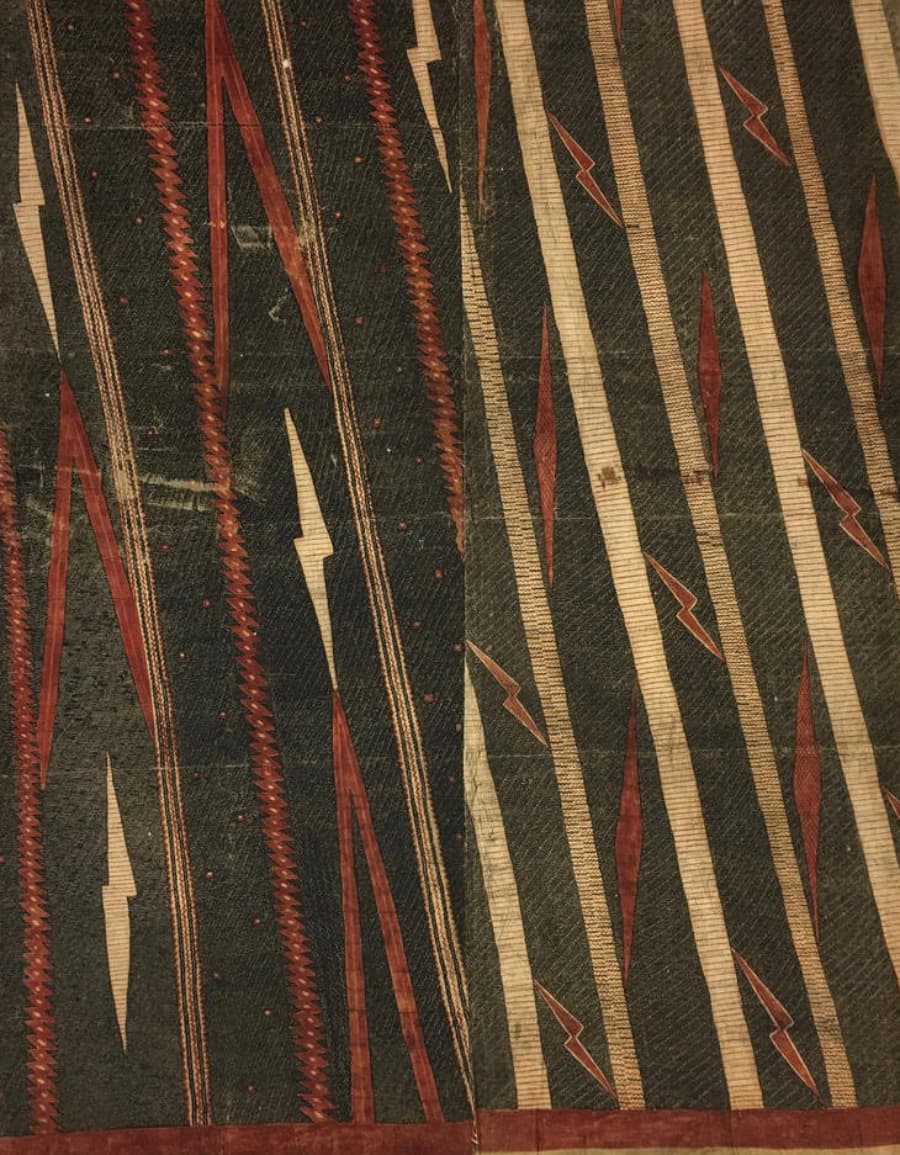

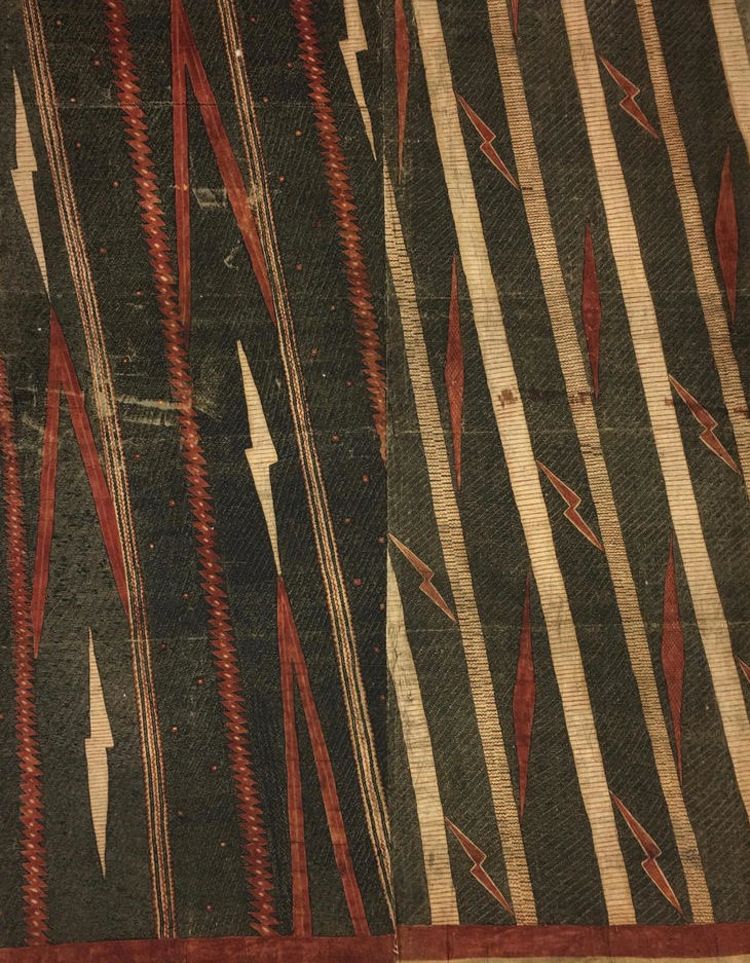

Lapa are carved from ʻohe (bamboo), a kinolau (physical form) of the god Kāne. They can be a single knife-like blade or a fork-like instrument with anywhere from two to ten tines that can vary in width and spacing. Lapa (aka “liners”) are dipped into inks and moved across the surface of a kapa to create designs.

Photo: Bishop Museum

Photo: Bishop Museum

There are over 150 lapa in the Bishop Museum's collection. Nearly a third of them have four tines, but lapa with five and six tines are also well represented. Angled tines allowed for angled lines between borders.

Photo: Bishop Museum

Photo: Bishop Museum

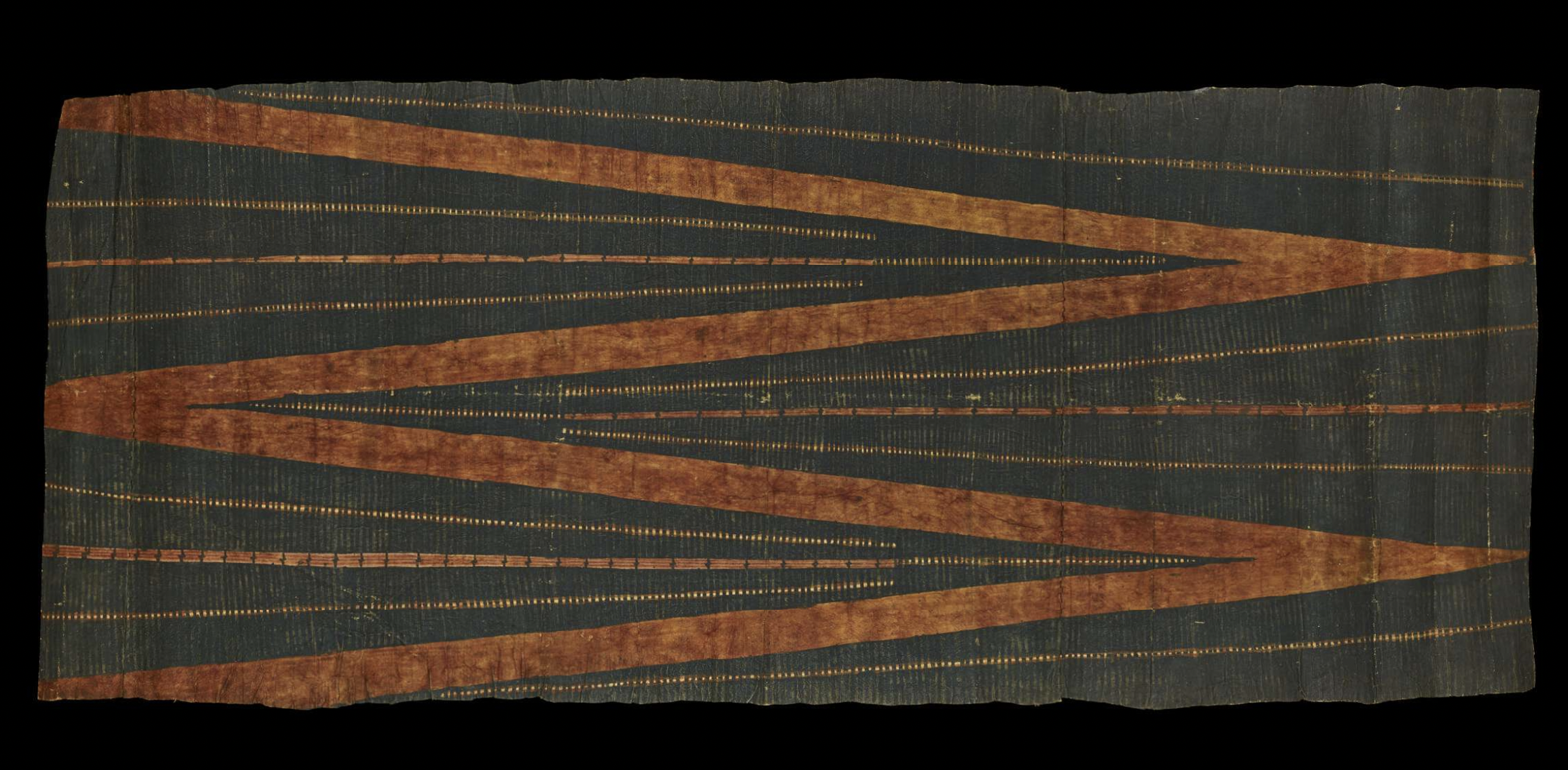

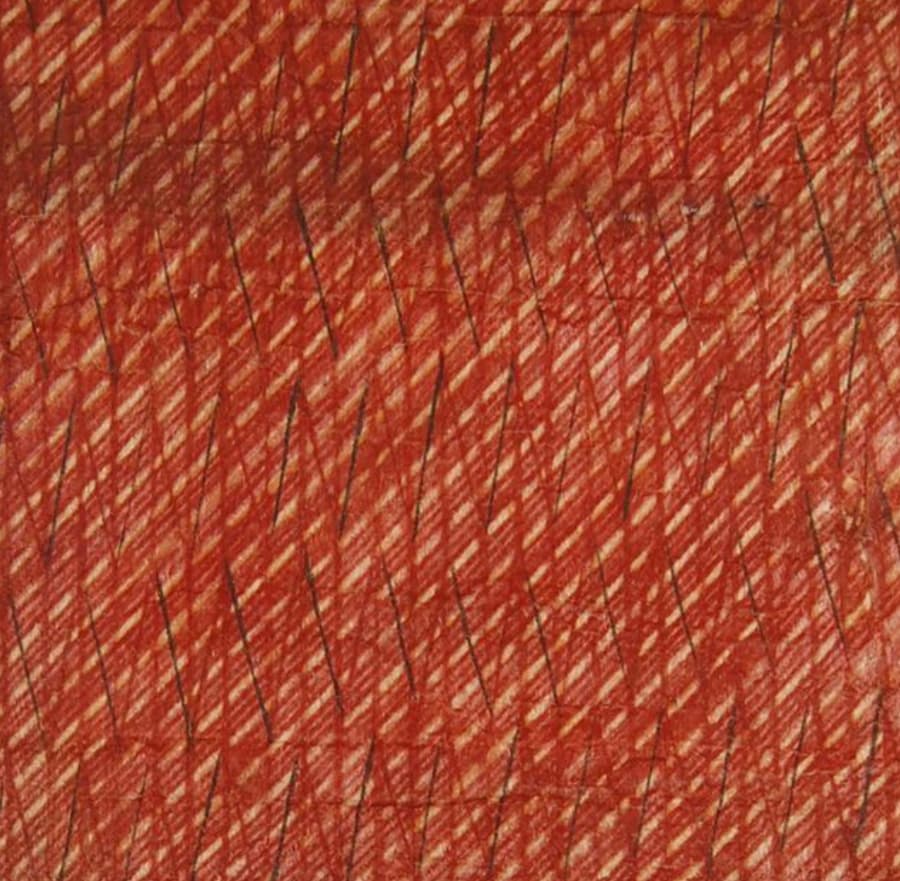

Some lapa have tines with very slight depressions that can hold a bit of ink. It wicks down as the lapa is moved across the fabric to produce lines, both straight and wavy. Dots are made using the tips of the tool, sometimes hundreds or even thousands carefully applied to a single piece.

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

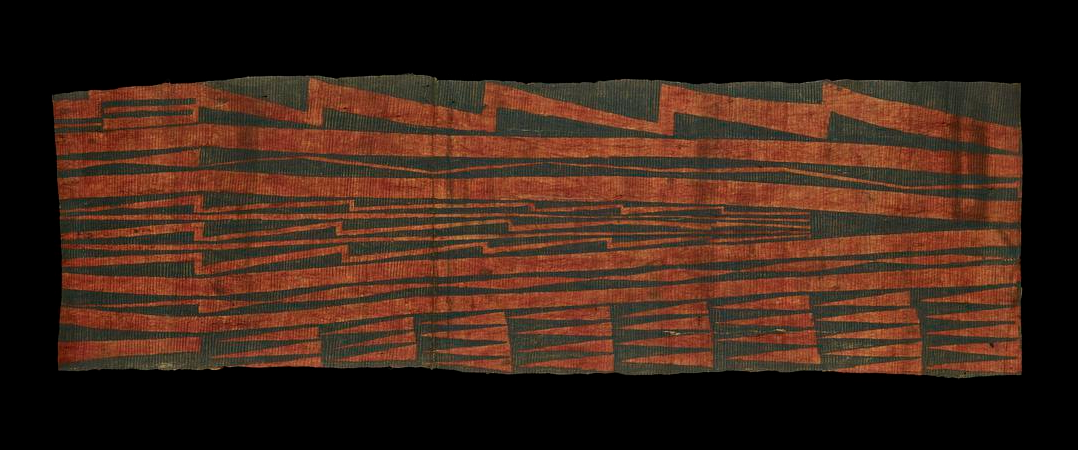

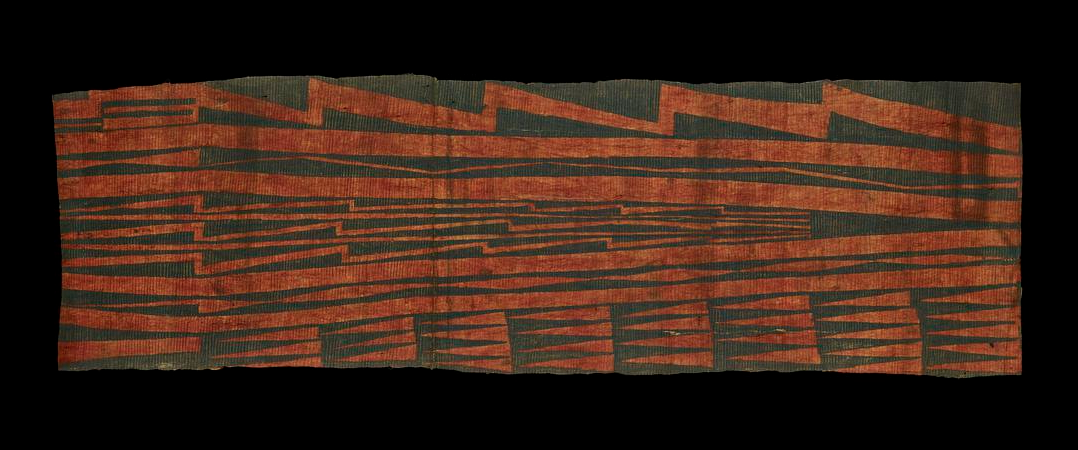

Possibly the most remarkable aspect of these pre-contact pieces is how the designers layered and combined lines, using them to fill bold geometric shapes, oftentimes in painstaking detail. It is that larger design layout, often across many feet of barkcloth, that boggles the mind.

Loea (skilled kapa makers) of this time cleverly used both symmetry and asymmetry to keep the eye and the mind engaged. They elegantly employed negative space in the layout of some designs, allowing the plain barkcloth to show through, its creamy color the lightest in a limited palette of bold, earthy tones.

The designs range from bombastic to delicate, all in a single piece. A variety of styles are represented, even amidst the relatively few works that have survived the ages. Imagine the staggering diversity there must have been 240 plus years ago when lapa was the main method of decoration. One of the most fascinating things about these pieces is that they show us a uniquely Hawaiian aesthetic, one born from shared Polynesian roots that likely evolved with very little other influence.

By now you are surely asking yourself how and why this method of design is not more visible or familiar. The answer is: it's complex.

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

‘Death of Captain Cook’ by George Carter. 1781.

‘Death of Captain Cook’ by George Carter. 1781.

Museum: Te Papa Tongarewa

Museum: Te Papa Tongarewa

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

Geography is the biggest issue. All of the pieces shown here live in museums overseas.

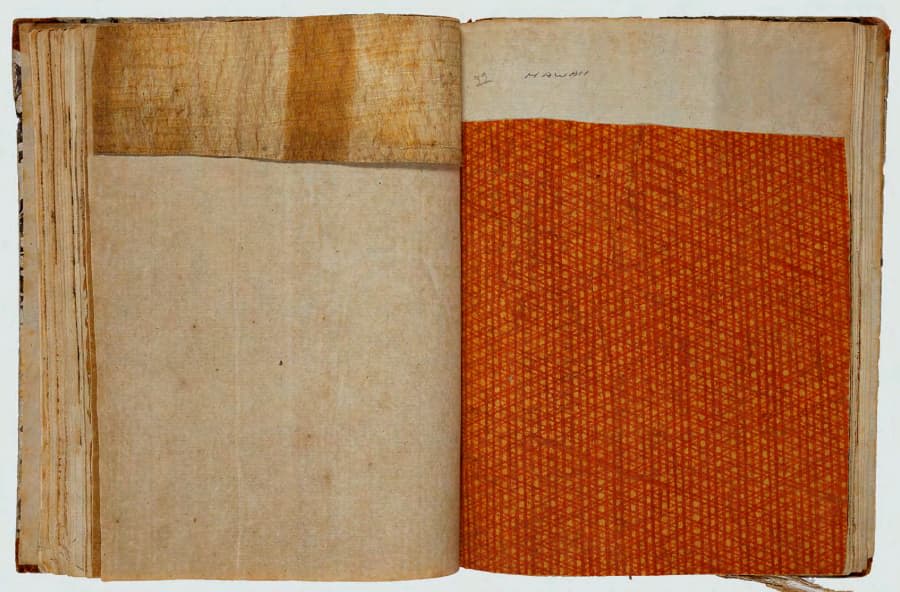

The best surviving examples of kapa decorated with lapa were collected during Cook’s third voyage into the Pacific, the first of his visits to Hawaiʻi being in 1778. These pieces have been carefully preserved for nearly two and a half centuries, but they live in lands very far from Hawaiʻi - so far that most Hawaiians will never be able to see them in person.

‘Death of Captain Cook’ by George Carter. 1781.

We are left to connect virtually with these treasures, through websites and photographs. This is the bittersweet reality facing kapa makers and anyone seeking to connect with the artistic brilliance of those who went before. It's amazing to even know these works of art exist, yet gutting that we cannot truly experience them.

We know little to nothing about why certain pieces of kapa were selected and exactly who “gifted” or exchanged them with Cook and his crew on Kauaʻi and Hawaiʻi.

One possibility is that they came from stashes of unworn kapa that aliʻi (chiefs) had on hand. Personal garments they actually wore would have been highly guarded, as were all mea pilikino (articles associated with the body) because they were imbued with a person's mana.

Museum: Te Papa Tongarewa

During makahiki, tributes were collected up and often redistributed in chiefly circles. Aliʻi were likely free to keep the choicest kapa from a number of makers and give the rest to their retainers and others who worked in service to them, whose food and clothing they provided.

It’s also plausible that aliʻi with productive lands and ample material comforts could have retained the highest level kapa makers and designers to produce garments exclusively for them.

There are also several accounts of aliʻi making kapa themselves, such as Nāhiʻenaʻena.

However it went, some incredible works of art wound up with Cook and his crew. Amazing minds and skilled hands conceptualized and crafted these early pieces. Many contemporary kapa makers and students of Hawaiian design have yet to study this early form, to understand what this striking and marvellous visual legacy seeks to communicate.

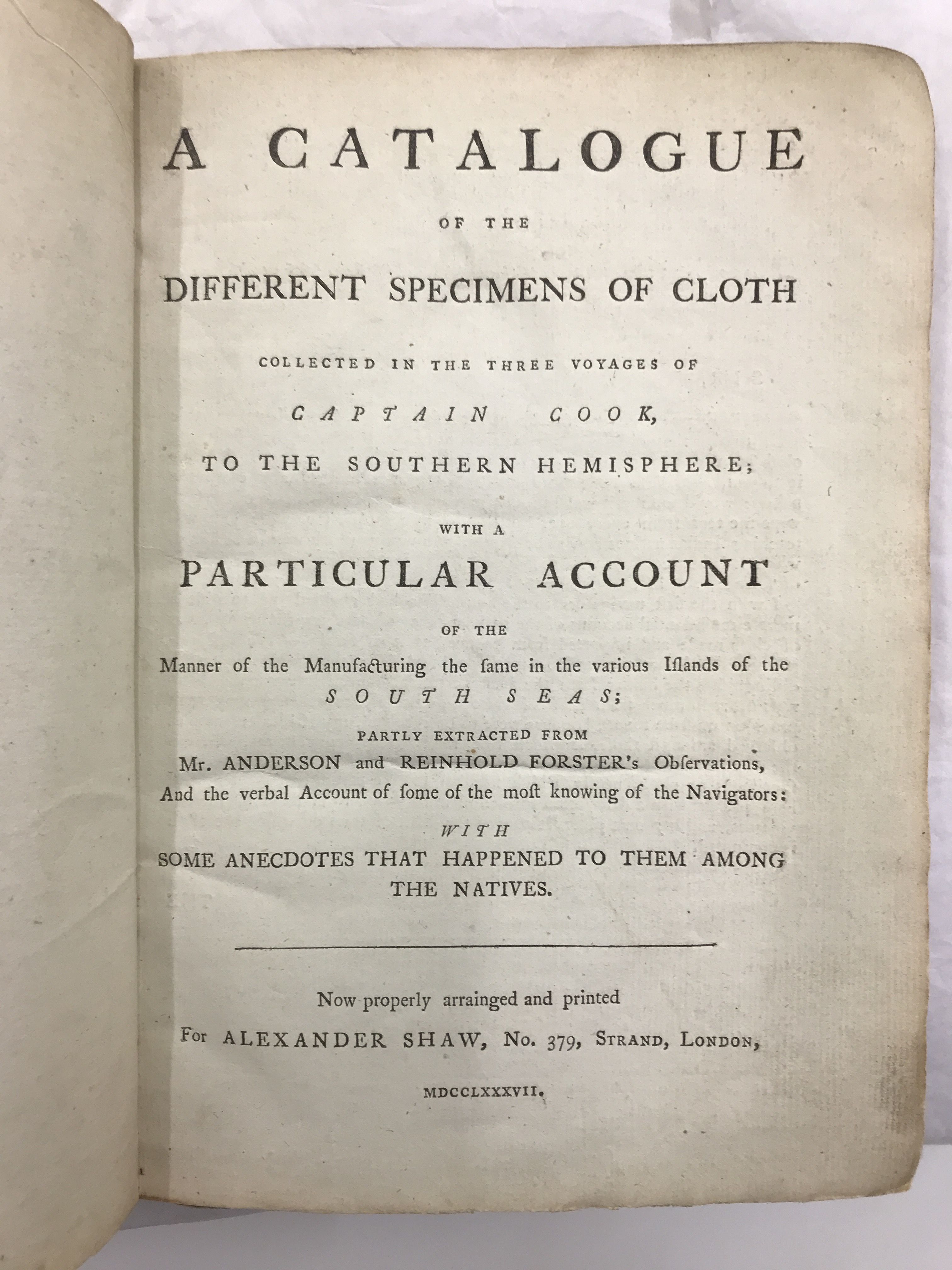

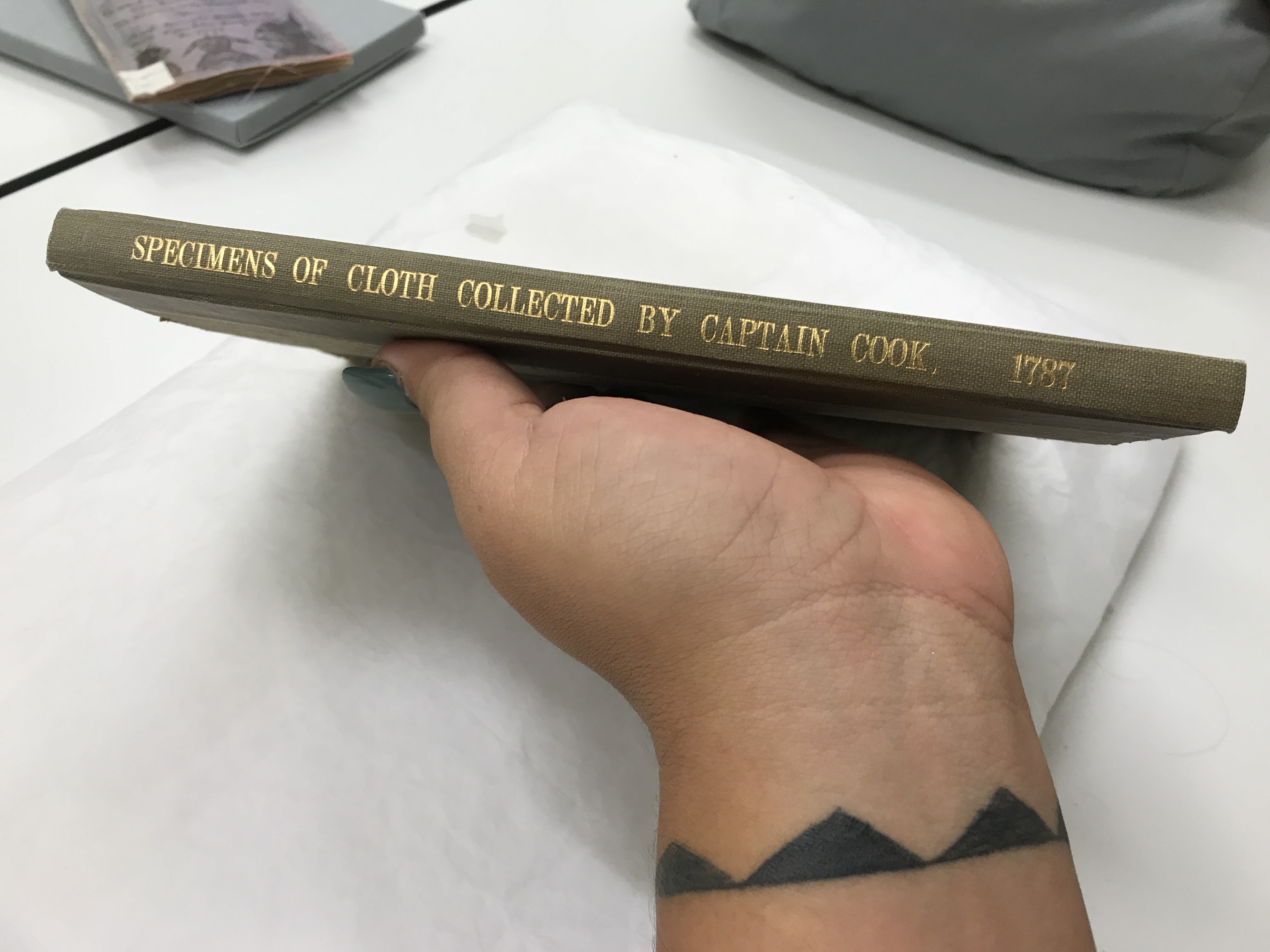

Photo: National Museum of Scotland

That discovery and connection is made increasingly difficult by the fact that after these old pieces were taken back to Europe, some of were preserved, while several others were eventually dismembered. Alexander Shaw was likely a London book seller who may have acquired some of the kapa from David Samwell, the surgeon’s mate on Cook’s third voyage, at a sale Samwell had in 1781. Shaw later cut the kapa into pieces and spread them across several bound volumes that he sold. These trophy barkcloth collections have ended up all over the globe. There are 66 and counting, according to a census done by Donald Kerr in 2015.

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

Photo: Hinaikawaihiʻilei Keala

This photo is not a Shaw book, but another example of dismembering barkcloth for trophy samples. Photo: British Museum.

This photo is not a Shaw book, but another example of dismembering barkcloth for trophy samples. Photo: British Museum.

The practice of creating "sample books" caught on in many institutions, even at home in our very own Bishop Museum. Curators and researchers of the past were comfortable allowing kapa to be dismembered or have samples removed. These days, there are curators who are also cultural practitioners and they approach collections in a completely different way. Folks like Kamalu du Preez dream of "re-membering" these old pieces so that the larger design aesthetics can be studied.

“We’re not a flip book. If you want to know what Hawaiian Kapa is, you have to see the whole piece.”

Such rejoining of disparate fragments of larger pieces is difficult within a single museum and even harder across institutions, but it isn't impossible. It would provide invaluable ʻike (information) for workers today who seek to truly understand how our forebearers approached design.

Another possible reason for our disconnection from this part of kapa making is that we are still in recovery mode.

Kapa was revived from the very edges of kanaka consciousness and lovingly nurtured by a relatively small community of folks. Those early workers were willing to push through the high barriers to entry: the need for native or similar hardwoods, knowledge of woodwork or access to a carver, land and water to grow wauke which must be lovingly tended for 12-18 months, and, above all, large swathes of free time. Many Hawaiians have little or no access to these things.

Photo: British Museum

Those with time and resources have poured their aloha into recovering the ʻike (knowledge and experience) needed to continue growing the practice and have worked hard to create pathways for others to enter who might not have had the means. Yet, even their time and access to historical pieces has limits.

Recovery of any Hawaiian practice has both joyful and difficult aspects. Many of us have to overcome feelings of being less knowledgable or talented than our illustrious ancestors and just go for it. We push past insecurities and other barriers, knowing the actual work is far more important and must happen if we are to do right by them.

Once solid ground is underfoot, it is easy to work inside familiar boundaries. However, new vistas open as we move forward in time, so the willingness to continually broaden our scope allows for the exciting growth and evolution of this collective recovery; a dynamic process that asks for our constant flexibility.

ʻOhe kāpala has become familiar and comfortable territory. Old motifs have even been refashioned into designs for modern clothing. Folks young and old carve and use kāpala with confidence and ease. However, the same probably cannot be said for lapa, at least not on the same scale.

Photo: British Museum

Which brings us to our last and final supposition about why lapa has not featured widely in modern kapa: it's not easy! Every kapa maker knows how daunting it is to decorate a piece of kapa into which they've invested potentially 18 months of grow time (if they farm their own wauke) plus hours of processing, beating, and softening. It takes so much just to get to the place where you are ready to apply design.

Inks can be carefully brushed onto ʻohe kāpala and applied with little mess or fuss. Lapa, on the other hand, requires one to manage the flow of ink down several tines and constantly reapply to a running set of lines, risking blobs (a highly technical term) and inconsistencies. It's uncomfortably tricky and hard to control. At the same time, it's a fascinating challenge to working with the boundaries of linear design native to lapa. Pieces like the ones above show us just how ingenious and creative kapa makers of the past were. They produced miraculous masterpieces with seemingly simple tools, taking lines to another level.

Photo: British Museum

Wouldn't it be wonderful to see lapa brought back into the broad scope of kapa making? As a pre-contact Hawaiian visual language and technique, it is certainly worthy of study, admiration, discussion, and re-development by workers today. To see lapa being carved alongside ʻohe kāpala and used by folks tackling large-scale designs on malo, pāʻū, and kīhei would be awesome.

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: British Museum

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

At Kealopiko, we are constantly seeking to understand more about how our kūpuna related to life and how they represented that through design. This requires us to look and listen back with new eyes and ears.

We began our foray into kapa designs by highlighting watermarks, which we understood as a defining feature of Hawaiian kapa. We then learned they exist in Indonesia, as well, and that the practice is not exclusively ours.

We also understood that Hawaiian kapa was, of course, retted so it could hold the delicate watermarks carved into iʻe kuku (square beaters). Then we came upon evidence of women's malo worn for lele kawa (jumping from cliffs into the sea) and swimming, and we were forced to expand our perception to include fresh beating (termed wai liʻiliʻi by some) and everything in between. This was supported by the difference in fabric textures and organizations of fibers in kapa we saw at the Bishop Museum. It makes so much sense that our ancestors would have had a range of processes to produce a variety of kapa types for several different purposes.

As we kept following the fibers deeper into history, we eventually wound up in the wonderful world of lapa (mahalo, e Lisa Raymond, for opening that door). We were stunned, incredulous that there was this whole realm of kapa design we knew nothing about.

Lapa with various numbers of tines used with a bamboo straight edge lent itself to the mastery of lines, which is really the heart of this aesthetic. It wasn't until we began researching pre-contact kapa that we witnessed the mastery of these kūpuna for ourselves and decided to pay tribute to that through design. The lapa stripes collection is our modern take on their love of lines.

We also fell in love with the "kapa uila" featured here which was one of a handful of those Cook voyage pieces that really caught our attention. Over the years we have almost exclusively created original designs, so choosing to replicate this old piece was an intentional departure.

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

We wanted to pull this dramatic and stunning creation back into the collective consciousness. We believe it represents a high point in the development of this bold and beautiful aesthetic so long removed from our experience, this visual language that has been deeply tucked away in the folds of space and time.

Photo: Bernisches Historisches Museum

But it isn't just the creative mindset or the optical feast that stopped us in our tracks and motivated us to highlight this piece. It's the aloha and the hoʻomanawanui (patience and capacity) that it takes to create something with this level of detail, the hours of focused dedication. He haʻawina nui ko laila e paʻa ai ko kākou ʻike ē, he maiau a he mikiʻoi ka Hawaiʻi.

We hope that seeing these kapa kupuna decorated with lapa inspires you and brings new beauty into your world. We also hope that it stimulates conversations about history, identity, access, recovery, and practice. What creative horizons await when we begin making and using lapa again? E ō mai, e nā hoa kuku kapa!

Photos: British Museum and Museum of Scotland

Photos: British Museum and Museum of Scotland