Ancient Adzes & Modern Makers

Awaiaulu Creates Tools and Toolmakers to Access Hawaiian Knowledge

These days we call them "hammers" (pronounced "hammahz"): people who work hard, know plenty, make things happen, or smash competition. In old Hawaiʻi there were many hammahz, or powerful individuals, but not the tools called hammers. Hawaiians had koʻi, adzes for carving important things and making other tools as well. Many of the hammahz, or koʻi, if you will, of our history are not well known. Their rich and fascinating stories sit in the forest of Hawaiian-language writings left by our kūpuna, waiting to be carved out.

A Hawaiian koʻi in the collections of Te Papa museum in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Awaiaulu is a modern-day koʻi that hews out the stories of the past and makes new koʻi, or skilled people, who can do that hewing today and carry it on into the future. A non-profit organization dedicated to providing access to Hawaiian knowledge, Awaiaulu hones the skills of fluent scholars through translation training, while also bringing forth Hawaiʻi’s history of hammahz through time. A fitting symbol for this is ʻOlopū, the ancient koʻi that empowered chiefs all the way up to Kamehameha, the great unifier of Hawaiʻi.

Carving out the past

The most famous of the koʻi, Kamehameha I laid the foundation of our modern nation. We hear about his big battles and how he used guns and foreign weapons to unite the islands under his rule, but very little is known about the other tools that contributed to his success, such as koʻi. Prowess, strength, and determination helped, but he needed the knowledge of those who came before him to make his most important endeavor take flight, earning him the name Kaʻiwakīloumoku (the ʻiwa bird that strings together the islands).

We might think of ʻike (knowledge) as something transmitted from one person to another, but objects can also hold accumulated ʻike and mana (power) in them. ʻOlopū was one such object and this is likely why Kamehameha went after it. His pursuit of this koʻi and its significance sat silently in the forest of our history, until hewn out using the research and translation skills taught at Awaiaulu. What follows is a short story of this fascinating tool that was prized by many hammahz of the past.

A Hawaiian koʻi in the collections of Te Papa museum in Aotearoa New Zealand.

A Hawaiian koʻi in the collections of Te Papa museum in Aotearoa New Zealand.

ʻOlopū, ke koʻi haʻi kūpuna, ke koʻi kua honua, ke koʻi kua moku ʻāina, ke koʻi naʻi aupuni

ʻOlopū, the adze that tells of genealogy, shapes the earth, hews out islands, and creates a nation

Black as the deep pō (generative darkness) and with star-like density, the stone used to make ʻOlopū came from the clashing of gods; the meeting of a volcanic eruption with a glacier. This specific run-in of Pele and Poliʻahu atop Maunakea produced some of the finest basalt in the Pacific. Hawaiian adze makers recognized the supreme quality of this specific layer of stone, quarried it extensively in a place they named Keanakākoʻi, and used it to make a range of koʻi big and small.

This and above photo: Various koʻi from the Bishop Museum collection.

This and above photo: Various koʻi from the Bishop Museum collection.

It may have been Wākea who fashioned ʻOlopū. One old chant talks about him as the whetstone worker, using sand and snowmelt from Maunakea to grind and sharpen the stone. ʻOlopū was used to carve Wākea’s own canoes and was handed down through the generations of chiefs, namely those of Hawaiʻi Island. With it they consecrated their most important work projects, like carving images for temples and making canoe fleets, endeavors that grew and maintained chiefly status.

ʻOlopū was eventually inherited by Hawaiʻikuauli, son of Lilinoe and Kūkahauʻula. In their deity forms they appear as the mist and fine rain of the mountain, and the snow in the red glow of sunset. In her human form, Lilinoe was a famously beautiful chiefess raised in isolation in a cave on Maunakea where she drank the water of a spring called Poliʻahu. One story says Kamehameha’s name honors Lilinoe’s upbringing in a solitary place (ma kahi mehameha) on this mountain of great importance whose sacred peak is the highest point in the Pacific.

Kūkahauʻula. Photo by Kahoolemana Naone via the Instagram account @naneaarmstrongwassell

Kūkahauʻula. Photo by Kahoolemana Naone via the Instagram account @naneaarmstrongwassell

ʻOlopū surfaces again during Kamehameha's rise, the ascent of this warrior chief whose mother craved the eye of the tiger shark when he was in her womb. A thief had torn apart the special storehouse where ʻOlopū was kept and taken it to Maui chief Kalanikūpule. When the news reached Kamehameha that this koʻi of great mana and antiquity had been stolen, he traveled to Maui to find it. This was a convenient pretense for waging war on Kalanikūpule.

At the battle of Kawaʻanui, named for the purported 8,000 canoes that covered the shores from Hāmoa to Kawaipapa, Kamehameha’s forces defeated a battalion under the command of Kapakahili. He was one of Kalanikūpule’s generals and he had ʻOlopū in his possession. When Kapakahili fell in this clash of forces, Kamehameha took hold of this koʻi naʻi aupuni, this nation-building adze, and build a nation he did. He went on to win most if not all of his subsequent battles and bring the islands under his sole rule, creating the foundation of our modern nation.

He aupuni ko Kamehameha.

Kamehameha has a government.

A warning not to steal.

Kamehameha united the islands and made laws that gave everyone peace and safety. Killing and stealing were utterly prohibited.

Many different koʻi were used to carve the tools Kamehameha used in his quest: massive canoe fleets, various Kū idols, thousands of weapons for his warriors. Certainly koʻi were used to fashion the images that stood on Puʻukoholā, the heiau he erected as per the advice of the kahuna who prophesied his rise to power. Yet, this one koʻi stands apart from the rest. Why?

ʻOlopū is a called the “koʻi haʻi kūpuna”, the adze that tells of genealogy, of the many ancestors who held this same koʻi in their hands during their own rituals and battles. Its presence at these times means it carries in it their chants, prayers, and language. It is this accumulated ʻike (knowledge and experience) that made this koʻi so special. When it came into Kamehameha’s possession, it linked him all the way back to Wākea, one of our most remote ancestors. ʻOlopū is even mentioned in chants for Kamehameha's descendants of the kingdom era, calling forth its mana into their leadership. For ʻOlopū to have survived the ages, absorbed their mana and come into the hands of this chief now well known to people both inside and outside of Hawaiʻi is truly amazing. Where this koʻi lies now is the last part of its story that needs to be discovered.

A Hawaiian adze that once belonged to Emma Nakuina. Photo: bonhams.com

A Hawaiian adze that once belonged to Emma Nakuina. Photo: bonhams.com

Hilinaʻi Sai-Dudoit with his mother, Kauʻi Sai-Dudoit, and Puakea Nogelmeier, the two kumu of Awaiaulu. This is the work room at Hakaʻolu, the heart of Awaiaulu's operations.

Hilinaʻi Sai-Dudoit with his mother, Kauʻi Sai-Dudoit, and Puakea Nogelmeier, the two kumu of Awaiaulu. This is the work room at Hakaʻolu, the heart of Awaiaulu's operations.

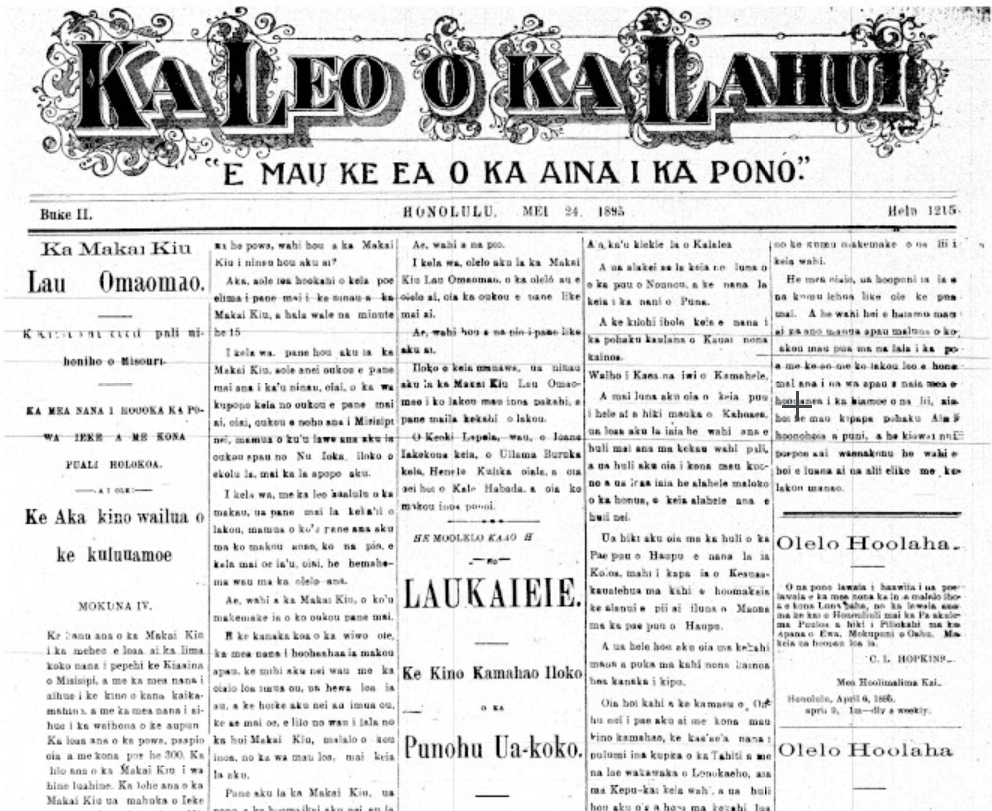

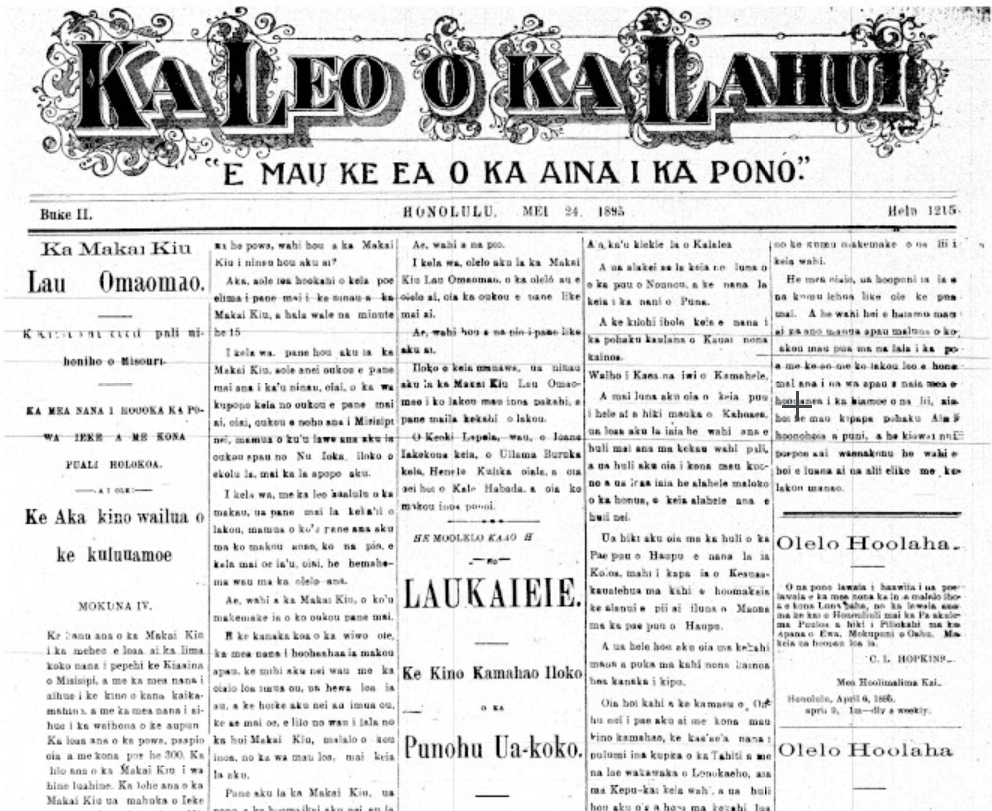

An example of the over 100 Hawaiian-language newspapers that ran from the 1830s to the 1950s.

An example of the over 100 Hawaiian-language newspapers that ran from the 1830s to the 1950s.

Trainer Haʻalilio Solomon has been with Awaiaulu since 2015. He is in his third project and runs a team with two other translators. He is shown here in the studio of KTUH 90.3 FM, where he hosts the show Kīpuka Leo.

Trainer Haʻalilio Solomon has been with Awaiaulu since 2015. He is in his third project and runs a team with two other translators. He is shown here in the studio of KTUH 90.3 FM, where he hosts the show Kīpuka Leo.

Awaiaulu at the International Conference of Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC).

Awaiaulu at the International Conference of Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC).

Carving out the future

This account of ʻOlopū was hewn from the raw materials of Hawaiian language that our kūpuna intentionally left for us. Just like ʻOlopū, these writings have also survived the ages, hold in them the mana of those who wrote them, and have now come into our collective grasp. Thanks to the important work projects of Awaiaulu’s founders, much of this huge cache of writings has been digitized and made searchable online.

Hilinaʻi Sai-Dudoit with his mother, Kauʻi Sai-Dudoit, and Puakea Nogelmeier, the two kumu of Awaiaulu. This is the work room at Hakaʻolu, the heart of Awaiaulu's operations.

A koʻi for carving creations from these raw materials consists of two main pieces. The stone is a knowledge of language that must be quarried and turned into a preform - a blank with the rough shape of a blade. This needs to be ground down, polished and lashed to a handle, a backbone of history that can help to direct its strikes, give them purpose and accuracy. We could say that the cordage for lashing the two together is a knowledge of translation, the ability to bridge between one language and another.

The metaphorical grinding, polishing and lashing of koʻi is the work of toolmakers Puakea Nogelmeier and Kauʻi Sai-Dudoit at Awaiaulu. Dedicated to spreading Hawaiian knowledge, Awaiaulu creates resources and resource people. They specialize in teaching the art of translation so that the knowledge in the writings of our kūpuna can be accessible to all.

An example of the over 100 Hawaiian-language newspapers that ran from the 1830s to the 1950s.

Each week, students at Awaiaulu are given pieces to translate individually. They meet with their team members to review their draft translations, then again with Puakea to further polish and refine each piece. Kauʻi provides guidance for historical context and helps students to construct a fuller understanding of the material.

Each final translation is the result of many rounds of revision and much careful consideration. This process creates tools and toolmakers. Students come with their rough preforms and leave with a koʻi (or several, depending on how long they train) that can do the work of carving useful things from the vast forest of knowledge left by our ancestors. Awaiaulu is the only organization in Hawaiʻi that offers this kind of training.

It is our birthright to know the stories of the hammahz, or koʻi, as we prefer to call them, who opened the path we walk today. Kamehameha, who laid the foundation of our modern nation with tools like ʻOlopū, is just one of so many fascinating and accomplished people who came before and after him. Much of this knowledge has been available only to those who know Hawaiian language, but that is changing now.

Trainer Haʻalilio Solomon has been with Awaiaulu since 2015. He is in his third project and runs a team with two other translators. He is shown here in the studio of KTUH 90.3 FM, where he hosts the show Kīpuka Leo.

Are the stories more ʻono in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi? Of course. No translation can unlock ALL the flavor and wisdom in a piece of writing. It is the hope of the kumu and haumāna at Awaiaulu that tasting moʻolelo (stories and history) in English will make you ʻono to taste them in Hawaiian, that it will be fuel in your language-learning engine.

With this design for ʻOlopū, Kealopiko celebrates Awaiaulu’s creation of koʻi that open access to our history, language, and the cultural wisdom therein - our most uniquely powerful tools in this modern era. Fashioned with aloha and through hard work, these koʻi can help carve our paths into the future.

Awaiaulu at the International Conference of Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC).

Click here to visit the Awaiaulu website and learn about their translation training programs. Click here to go straight to their awesome list of resources for researching Hawaiian language and history.