Ka ʻOno o Ka Lihi Kai

Talking ʻopihi and the intertidal community

with Uakoko Chong

ʻOpihi are one of our most treasured iʻa and a new generation of kanaka is doing the work to make sure all our descendants can enjoy them.

In celebration of a fresh release of our ʻopihi design, we interviewed researcher and mālama ʻāina Autumn Tehani Uakoko Chong. Hailing from Puʻukapu, Waimea (Hawaiʻi Island), Uakoko's parents instilled in her a love of the ocean from a young age.

That aloha was nurtured in Ke Aho Loa STEM Program and by Pelika Andrade at Nā Kilo ʻĀina, where where kānaka engage in kilo to develop their consciousness of place to support ʻāina momona: productive and thriving communities. Although Uakoko now works mostly up uka (on dry land) for huiMAU, we asked her to share about her love for the ocean and what she learned about ʻopihi during her time of working at the lihi kai (the intertidal zone and shoreline).

No hea mai ʻoe?

(Where are you from)

My ʻohana comes from all over, but we mainly grew up in Waimea, Kawaihae, and also down Waipiʻo. My dad grew up in Waimea, ranching, then they would go work in the loʻi in Waipiʻo. So, in the mornings they would be down in the valley, huki kalo and clean down there, then they would come back up to Waimea, fix fence and all that kine. Growing up, that’s where our ʻohana loved to be—in the kai. My dad worked a lot, so on his days off, he always made sure that we went to the kai.

Puʻu Hāloa nd Puʻu Kaʻala, Waimea. Image: Anianikū Chong

Uakoko and her ʻohana.

Loʻi kalo, Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

What are some of your favorite memories of being with your father in the ocean?

I’m one of two girls in our family and I also have four brothers. When we were young, my father taught them more about diving and holoholo and me and my sister would be on the shoreline and in the kāheka (tide pools) with our bamboo poles. When we got older, he started to take me and my sister out to go diving. He had the tako (octopus) eye! He learned from his cousins growing up and that’s one of the special gifts he passed on to us. I remember always going home with tako and iʻa—just enough for our ʻohana.

A lot of my memories with Dad are just learning from him, one breath at a time, how he moves under the kai, so patient and serene. To have my dad model that for us taught us about lawena, how to carry ourselves and behave, and also about feeding ʻohana. That’s what I want to make sure we teach the muli (younger generations).

Uakoko and her father, Alvin ʻEkikiela Chong Jr.

Uakoko and her father, Alvin ʻEkikiela Chong Jr.

A lot of my memories with Dad are just learning from him, one breath at a time, how he moves under the kai.

He wasn’t much of a talker. It was always just watching him. If we were being too loud, he would scold us on the spot. If we had questions or he wanted to share something, he would wait until we were on the shoreline eating lunch or when we were back home. In the doing of gathering from the kai, he didn’t talk a lot. He just made sure we were set up and then he led us, showing us all the grounds that he learned growing up, all the different honey holes.

I kai o Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

Clearly the ocean is a deep part of your upbringing, but how did you come to work in the kai?

The summer after I graduated, my mom (Ursula Uʻilani Vincent) asked me a question. It was so beautiful the way she said it. She asked, ʻWhen you see yourself in an ahupuaʻa, where do you see yourself? And I said, ‘The kai. Automatic.’ Even outside of luʻu kai (diving), we used to make body boards and go surfing. I knew I loved being in the ocean and that it’s where I felt super comfortable. Soon after that conversation, Pua Lincoln asked me what I was going to do and she told me about a program called Ke Aho Loa, which led me to Pelika Andrade and Nā Kilo ʻĀina. It was those little conversations with my mom and the aunties in my community that really helped me to get to where I am today. I still think about that.

When you see yourself in an ahupuaʻa, where do you see yourself?

Puʻu Hāloa nd Puʻu Kaʻala, Waimea. Image: Anianikū Chong

Puʻu Hāloa nd Puʻu Kaʻala, Waimea. Image: Anianikū Chong

Uakoko and her ʻohana.

Uakoko and her ʻohana.

Loʻi kalo, Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

Loʻi kalo, Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

I kai o Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

I kai o Waipiʻo. Image: Anianikū Chong

Waipiʻo Valley, Hawaiʻi.

Waipiʻo Valley, Hawaiʻi.

After working at the lihi kai for over a decade, what are some of the insights you have gained about that ʻāina?

The beautiful thing about being with Nā Kilo ʻĀina and being on the shoreline with Pelika was that no matter the conditions—raging winter swells or whatever—we were still there to kilo and see what was going on. That was great because we could see what the transitions look like at the lihi kai over the makahiki (year).

I guess I want to talk about it in seasons, because you see so many things happening—the hot hot of the kau, then the wet, wind, and pounding waves of the hoʻoilo—so I’ll talk about it like that.

When I first started with Pelika in Kailapa, Kawaihae, we would go down to the bouldery beaches. We would scan the whole boulder and see who was living there. In late summertime, like August, there was not too much limu (seaweed), couple ʻopihi, some ʻina, some wana, and just lots of black. So, in summer, when it’s hot, the ʻopihi and other creatures hide and try to find shade in crevices or on the bottom of the rocks.

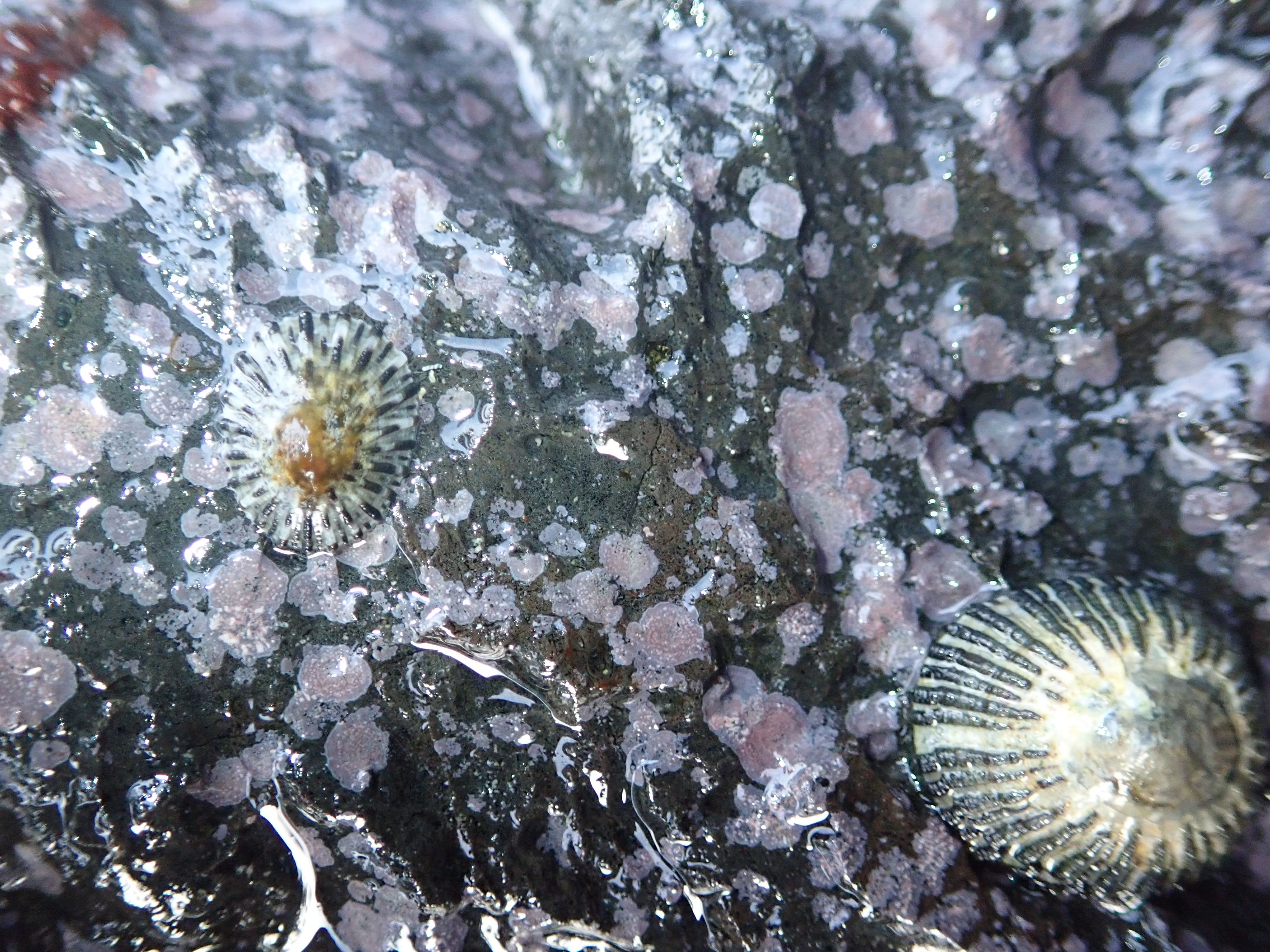

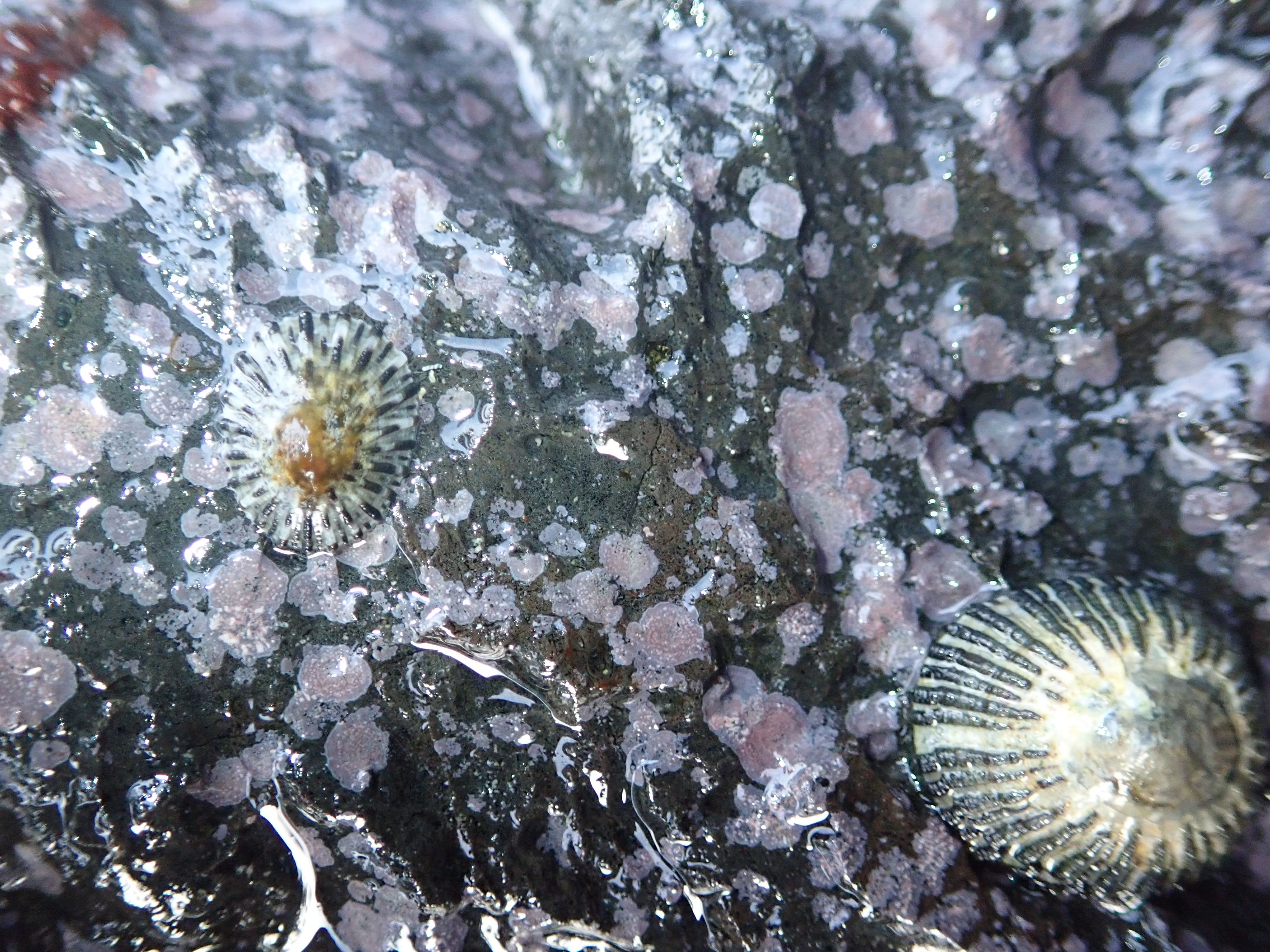

Ka lihi kai.

Then you go two or three months later, October into December, and you see the swells picking up and the ocean getting rough. You start to see pipipi and other iʻa gathering together more. When the swells and rains are raging, you start to see limu growing and the pink rock, which is a limu too. It starts as spots and blotches, then it crawls up and gets bigger, and then you see the pōhaku start to be covered in this pink rock. It’s made up of calcium carbonate, so it’s heartier than other limu. When it’s growing during the winter swells, it’s nice and pink, and when it gets hot in the summer it turns white and starts retreating.

During hoʻoilo (winter), you see this big increase of ʻāina on the lihi kai for all the different pūpū and iʻa to live in. That’s because of all the ua (rain) and the big waves that splash up farther, allowing all the iʻa in the intertidal zone to stretch out and extend how far up they can live.

When we were checking out ʻopihi at Kalaemanō, we started to see more baby recruits during hoʻoilo. When those big swells are happening, you don’t want to be over there getting ʻopihi, so it kind of becomes this natural protection for the ʻopihi, for the big ones to spawn and for the new recruits to come back in from the ocean.

New ʻopihi recruits.

I always look forward to the hoʻoilo and the season of Lonoikamakahiki because you see the growth and fertility happening along the shoreline too! There’s this cool cleaning system that the winter swells bring and the nalu flush out the kāheka during that time. After the swells mellow out, all the pua iʻa (baby fish) and limu begin to pop out. It’s that sort of hoʻoulu lāhui thing that you start to see happening on the shoreline with all different types of iʻa, not just ʻopihi. It’s a beautiful natural cycle.

That was the biggest lesson I learned—the cycles happening and why they are important. Also seeing that beautiful comeback of the whole community. It’s so cool to see all that growth happen in such a short time, and then by March and April you see the limu has grown really long and is swaying in the tide pools. Then it starts to go back into the summer and the hotter days.

But it’s that population—whoever makes it back to the lihi kai and survives through the summer—that’s gonna carry and hold on for the next generation of ʻopihi and limu to thrive when it’s hoʻoilo again. So, I appreciate those pūpū that are hammahz and make it back to the lihi kai, withstand the kau wela (summer), and are ready to reproduce for the next season.

What is a good size for eating to ensure the survival of this resource?

I can’t say for everywhere, because each area is different. I would encourage everyone to go learn their shorelines. Learn about the seasons of your iʻa. Go see when you can see baby ʻopihi, and check out when ʻopihi are full of gonads. Size matters. You want to leave your big mamas because the quality of their eggs are better and they have more of them. People have different uses for ʻopihi, and I’ve been to places where people like eating the big ones, but I don’t like eating the bigger ones. They’re tougher and more rubbery. I’m good with the smaller ʻopihi—they’re just softer and juicier.

What is the kuleana (role) of the ʻopihi in the lihi kai community?

ʻOpihi share the lihi kai with limu, other pūpū, wana, iʻa, heʻe pali, and even ʻākoʻakoʻa. I think of them as lawnmowers on the shoreline. The radula (rasping tooth) looks like a hedge trimmer, so they open up space and eat turf limu, which may be important for the babies to come back to the shoreline and attach onto the pōhaku.

What is the reproductive cycle of the ʻopihi?

ʻOpihi broadcast their gonads into the kai and only a small fraction of those come back to the lihi kai as recruits. Reproduction, the larval stage, and making it back to the shoreline takes about 15 days. I’ve seen some that were just getting going and the shell is super fragile. It will break if you push on it. I’ve seen them recruit in smooth areas, like boulders and pāhoehoe. Maybe the big ʻopihi that do broadcast spawn then clear the space for the babies to come back and recruit. When they get older, ʻopihi can figure out where their jam is, where they like be, but for the babies they like the smooth surfaces.

How are ʻopihi populations doing?

From the stories I’ve heard from talking with people, there’s definitely not as much. Heavy harvesting times are for pāʻina, graduation parties, and stuff like that. And it’s a great celebration to have all the different iʻa for your ʻohana at gatherings, but I do hear from a lot of communities and people who are ʻono for ʻopihi and haven’t had it in such a long time. That’s sad, because I don’t want for generations to forget that ʻono of the kai. I think that’s super important, but it also puts a kuleana on us to learn more about our shorelines: who’s there, how much you can take, the right times for taking, and when those seasons of resting are. Also, there’s all kine predators that go after them, like makaloa and pūpū ʻawa. These poor buggahs, they gotta survive from kanaka (humans) and all the pūpū over there. They have so much work they gotta do just to survive each season, so I have really come to appreciate them.

You’ve seen ʻopihi in the northwest Hawaiian islands. What is the difference between ʻopihi there and here in the main islands?

Ho, there were dozers up there! Big size and different color of shell. More brindled and ʻehu (reddish) looking. Beautiful! There was SO much ʻopihi. Everywhere you step, you might be stepping on ʻopihi. We went during September, so we got to see some baby recruits, too. But I just remember seeing how loaded the shorelines were and thinking that to see that back at home would be so beautiful.

Nihoa

What can ʻopihi teach us as kanaka?

Just being present on the shoreline is huge, and for us, being present in our community. ʻOpihi don’t live by themselves. They are surrounded by so many different types of iʻa that they have to interact and compete with. The ʻāina that they’re living in, they’re all sharing it and they all have to take care of it in order for their babies to thrive. So, holding that presence in your community, knowing your kuleana, learning when to spread out and jam, fulfil all your kuleana, but remembering to come back and feed your ʻohana and be ready for the next season and the babies to come. Through all the different challenges that you may face in your ʻāina, hold your presence in your space.

*This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Ka lihi kai.

Ka lihi kai.

New ʻopihi recruits.

New ʻopihi recruits.

Nihoa

Nihoa