Haumea & The Arc of Creation

Lessons from the original innovator

Introduction

From Makahiki 2022, to Makahiki 2023, we celebrated Haumea, the great mother who birthed our ʻāina, the abundance of life forms on it, and the stars in the sky that feed them. A single design alone does not do justice to this akua, our central female figure whose presence permeates the natural world and who is reborn in each generation (hānau wawā). For her, ua kualima ka hana - we created a series of five designs all honoring various aspects of her ʻano āiwaiwa (wondrous nature).

It is customary to begin with moʻokūʻauhau (genealogy), which was also the inspiration that sparked the research that led to this first design. It was a kanikau, a lamentation that included part of the Welaahilani moʻokūʻauhau. This mele clearly outlined a series of unions that Haumea had with six different moʻopuna (grandsons). In each case, she assumed a different form and took on a new name. We were fascinated by her actions and sought to learn more about her story and the significance of this series of piʻo (close relative) matings. The first design was then born: Haumea I. - Nā Moʻopuna.

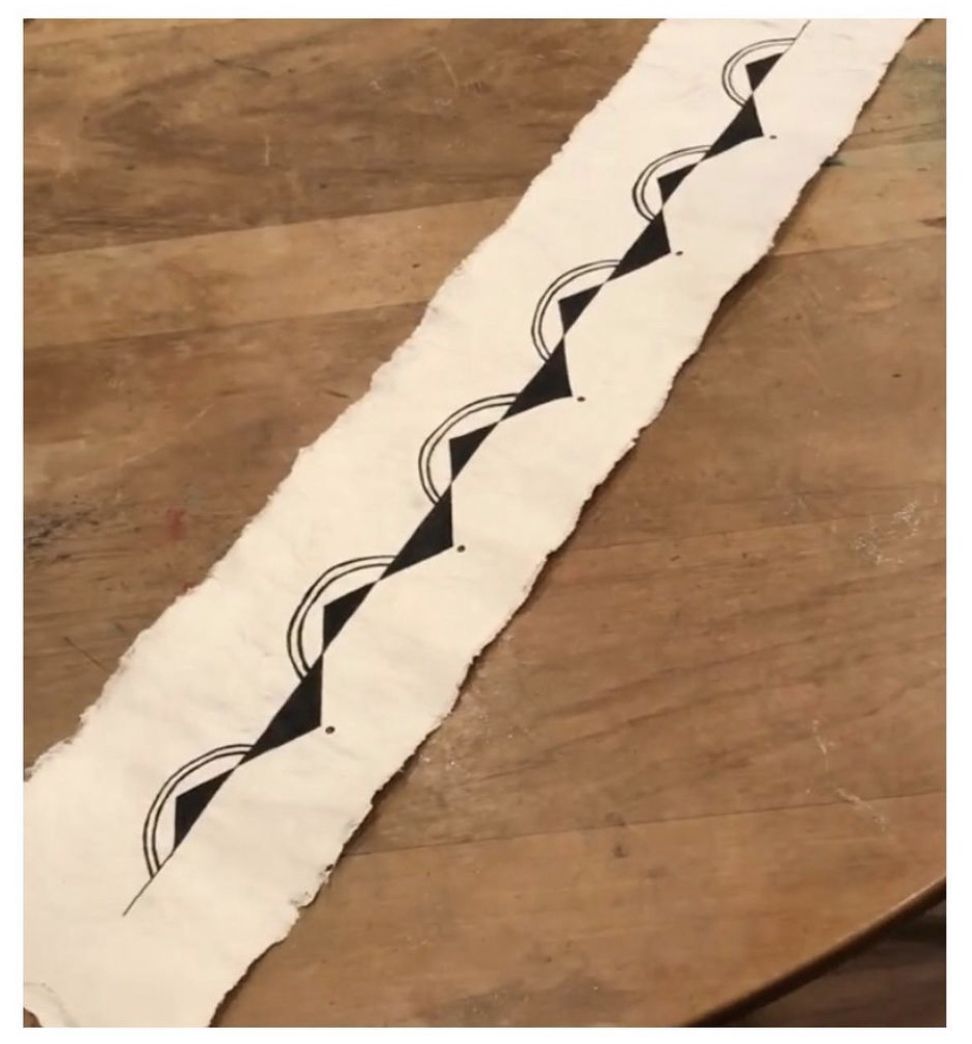

About this design: The horizon and the triangles that dip below it are representations of Papa/Haumea, the foundation, honua (earth), and womb of creation. Wākea, the male creative principle, is represented by the upward facing triangles reaching toward the sky like our highest mountain. The arches over the triangles represent the piʻo matings. Each time, Haumea leapt heavenward and then returned to earth in a new form, bringing back with her something important, which is why the arches begin and end on the earth. The piʻo also recall the ānuenue (rainbow), a traditional symbol of aliʻi who were the ultimate fruits of Haumea’s labor during this part of her story, which we share and discuss below.

Before we jump into the story, please know that topics like piʻo (the chiefly mating of close relatives) and ke kahe o ka wai ʻula (menstruation) are central themes in this moʻolelo. Also, the analyses offered below are based solely on your mea kākau’s (author’s) understanding of ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, interpretation of Haumea’s stories, and personal experiences as a wahine and makuahine observing myself and my community over time. Any errors or missteps are mine alone. The hope is that you will challenge or expand upon these ideas with your own ʻike (experience and understanding) as we grow our collective knowledge of this wahine akua. If you have thoughts to contribute, please send them to the email address at the end of this moʻolelo. Constructive feedback will be incorporated into this page so that our shared kālailai (analysis) may continue to grow.

"Hau is an essence. And mea can be seen as the earth, the red earth."

Like the kukui mālamalama (light of knowledge) that she was, Mary Kawena Pukui illuminated another meaning of Haumea's name in a quick comment to an anthropologist. Because she did not include this definition of hau in the Hawaiian Dictionary, this explanation sheds new light on this akua whose essence infuses so many aspects of life. Like the red dirt that runs in veins through the earth, the blood of genealogy flows as an unbroken river through the veins of every Hawaiʻi. And the flow of wai ʻula (womb blood; rain runoff red with soil) from wahine is what ensures the continuity of the generations, signaling the ability to carry on the moʻokūʻauhau of the ancestors. Originating from Laʻilaʻi, this “ancestral river,” as scholar Ngāhui Murphy calls it, and the realm of birth are Haumea’s eternal domain. Her stories and challenges as she births and produces within it give us a template for creation, change, and innovation as kanaka.

Each moon cycle, the wai ʻula begins a foundation capable of nurturing new life. Then it either flows out on the monthly tide, or welcomes the conception of a child and creates a honua (placenta). From that honua grows the hale ʻaʻa kanaka (caul) filled with the nalu (amniotic fluid) in which the child swims as it grows. From land to sea, wahine recreate the world inside themselves each time they grow a child in the ipu ʻaumakua (womb), much like Haumea who births ʻāina, akua, aliʻi, and kanaka.

This womb blood that enables women to be mothers is the tangible connection each wahine Hawaiʻi has to Haumea—the hau mea (essence of creation, if you will) inside all of us. It also provides a pathway for progress; when the red tide flows out, wahine can send down the river anything that isn’t serving them to make room for new things, including the insights that can come at this time if we are receptive. This cycle also mirrors Haumea’s own pattern of rebirth in her constant quest for innovation.

Haumea births islands as Papahānaumoku. It is one of many names carried by this wahine kino pāpālehu (woman of myriad forms). The child she is most well known for birthing is her daughter, Hoʻohokukalani, whose father is Wākea. He creates the diversion of kapu nights so he can be with Hoʻohokukalani and Hāloa is the child of their union. Less spoken about, however, is the fact that Haumea went on to have a child with Hāloa and with several other moʻopuna (grandsons). He was probably the second or third in a string of unions, indicating that Haumea had already started one of her most important projects in her legacy: creating the aliʻi bloodline.

Lili (jealous anger) is said to have been “born” out of Wākea having a child with Hoʻohokukalani (Kumulipo, line 1797), and rightly so—Papa may have been enraged at her husband for deliberately deceiving her in order to sleep with their daughter, as many versions of the story relate. However, rather than being solely an act of revenge, your mea kākau proposes that Haumea’s unions with her moʻopuna may have been an intentional decision on her part to build up her mana and her akua nature in them, making it possible for generations of aliʻi to come forth. In this phase of her creation, she brings much more than just the lili that is often mentioned in the unfolding drama between her and Wākea.

Prior to each of these matings, Haumea returned to the Haleopapa in Nuʻumehalani (also Nuʻumealani) where she changed herself into a beautiful young woman with a new name. She then returned to Hawaiʻi as a "new" wahine each time she took up with a moʻopuna. These six piʻo matings are mentioned in several mele and many writers make it clear that all these wahine are Haumea, the one shape-shifting woman who is known by a plethora of inoa.

The mea hilu loa (remarkable and mysterious thing) about Haumea’s matings with her moʻopuna is that they aren’t straightforward like Wākea’s union with Hoʻohokukalani. He did create a diversion so he could be away from Papa and with his daughter, but he did not fundamentally change who he was. Haumea, however, transformed herself completely. This mana hoʻopāhaʻohaʻo kino, or ability to take on various physical forms, that Haumea actioned in this cycle gives us a different starting place when we think about and interpret this series of relationships. Wākea did not have the mana to shapeshift, renew himself, or conceal his identity like Haumea did.

Why remake herself each time? Sure, part of it was a clever disguise so that her “true” identity was not discovered by her moʻopuna. But that answer seems too easy. Perhaps a more interesting question is: What does each of her forms add to the pool of mana that builds through these six unions? What does she contribute with each mating to the moʻokūʻauhau from which our highest chiefs emerge? Let us examine an old kanikau, one of several mele that tells this story. To help see the connections between generations, it is interwoven here with part of a genealogy for Kamehameha and another account by Poepoe (Note: It is normal for spellings of names to vary across chants)

Image: Anianikū Chong

Image: Anianikū Chong

Image: Anianikū Chong

Image: Anianikū Chong

ʻO Haumea nui a ke āiwaiwa,

A ke kalohe akua i nā keiki,

I ka iho nō Piʻo i nā moʻopuna,

I ka huli koke iho nō i nā keiki,

[Moe keiki iā Kauakahi, ʻo Kuaimehani ka wahine]

[Moe moʻopuna iā Kauahulihonua, ʻO Hulihonua ka wahine]

Moe moʻopuna kualima iā Hāloa,

[ʻO Hinamanouluaʻe ka wahine, ʻo Waia ke keiki]

Moe moʻopuna kuaono iā Waia,

[ʻO Huhune ka wahine, ʻo Hinanalo ke keiki]

Moe moʻopuna kuahiku iā Hinanalo,

[ʻO Haunuʻu ka wahine, ʻo Nānākāhili ke keiki]

Moe moʻopuna kuawalu nō iā Nānākāhili,

[ʻO Haulani ka wahine, ʻo Wailoa ke keiki]

Moe moʻopuna kuaiwa nō iā Wailoa,

[ʻO Hikawaopuanaiea ka wahine, ʻo Kiʻo ke keiki]

Iā Wailoa ʻo Haumea kapa i ka inoa ʻo Hīkāwaopuanaiea,

Hoʻi nō a Nuʻumehalani, ʻo ka lani kahi noho o ia wahine,

Paʻipaʻi i nā ū, kapakapa i ka inoa,

Papani ka wai o ke akua wahine,

Iā “Kiʻo” laha nā aliʻi,

ʻO ke keiki ia ʻike iā Haumea,

Hoʻi loa i kaulu o Nuʻumehalani,

Waiho iā "Kiʻo" i kumu aliʻi,

I make nō ke kinolau āiwaiwa,

He wahine akua kapu no Nuʻumehalani,

Kō kapu, e Haumea,

Eia lā—

"Noʻiau"

Honolulu

Most wondrous Haumea,

Of divine pairing with her offspring,

Who came down to mate with her grandsons,

Then quickly came back for her sons,

[She mated with a grandson, Kauahulihonua, as a woman named Hulihonua,]

She mated for a fifth time with a grandson, Hāloa,

[As a woman named Hinamanouluaʻe, Waia was the child of this union]

She mated for a sixth time with a grandson, Waia,

[As a woman named Huhune, Hinanalo was the child of this union]

She mated for a seventh time with a grandson, Hinanalo,

[As a woman named Haunuʻu, Nānākāhili was the child of this union]

She mated for a eighth time with a grandson, Nānākāhili,

[As a woman named Haulani, Wailoa was the child of this union,]

She mated for a ninth time with a grandson, Wailoa,

[As a woman named Hikawaopuanaiea, Kiʻo was the child of this union,]

It was Wailoa who gave her the name Hīkāwaopuanaiea,

She returned to Nuʻumehalani, the heavens are where this woman lives,

Struck her breasts [to stop the milk flow], changed her name,

The waters of this female deity were dammed up,

Through "Kiʻo" the chiefs became numerous,

He was the son who recognized Haumea,

She went all the way back to the heights of Nuʻumehalani,

And left "Kiʻo" as the source of chiefs,

Her marvelous forms ceased,

A sacred woman of akua status from Nuʻumehalani,

Your sacred nature, O Haumea,

It is known—

“Ua ola nō iā Haumea ka lei aliʻi o Hawaiʻi”

By combining the kanikau and the genealogy, it becomes clear that the keikikāne (male son) of each mating became the kāne (male mate) of the next, with the exception of the first union. These matings are termed piʻo by the composer of the mele, giving us a picture of several small arcs within Haumea’s larger journey. Haumea’s reappearance over these generations, each time in a new body with a new name, is often referred to as hānau wawā (“reincarnation”). Kiʻo was the last keikikāne to emerge and it’s said that he recognized Haumea and that is when this cycle ended. Kamakau says two kahuna from Oʻahu identified her, so perhaps they were the ones to inform this last son of his mother’s identity. She returned to Nuʻumehalani and left Kiʻo to father the generations of aliʻi, as seen in the last line above: “Iā Kiʻo, laha nā aliʻi” (Through Kiʻo, the chiefs become numerous).

If the name Kiʻo is concerning you, Kamakau says it refers to the buildup (kiʻokiʻo) of sap on the kukui trees in the uplands of Kalihi where Haumea and her family lived. This is fascinating when we remember how, as Kāmehaʻikana, Haumea transformed herself into a legion of woman warriors and defeated the forces of Kumuhonu by striking them in the foreheads with kukui nuts. Perhaps contrary to popular understanding, Haumea has the ability to both grant life and take it away, a theme that emerges again and again.

Another possible interpretation of the name Kiʻo could be the “pooling up” of mana that reached its fullness in this last keiki. Your mea kākau believes this buildup of mana is connected to the qualities reflected in each of Haumea’s inoa (names). The characteristics in the kāne names certainly bring to bear on this progression (and one wonders how naming went each time she took her son as her mate), but this story focuses on her forms.

All these inoa are worthy of study, as they help us understand Haumea’s larger story. They also give us insight into the many haʻawina (lessons and offerings) we can apply to our own lives as we relate, create, and seek balance in how we live as humans on Papa/Haumea, an earth with real limits. Her names are like pieces in the great puzzle of transformation, like lamp posts lighting the path of evolution. What follows are a few of the many possible meanings and interpretations associated with these Haumea names.

Kauahulihonua is the first moʻopuna with whom Haumea takes up. She comes to him as Hulihonua, a name that speaks of the overturning of earth, like a farmer preparing the soil for planting, helping to unlock its fertility. It also recalls the “nesting” that expectant parents do when awaiting the birth of a child. Any important endeavor requires careful preparation and sometimes change (whether peaceful or through conflict, as indicated in the name of this kāne) is necessary for new things to emerge.

If a new structure is to be built, it can only happen on a solid foundation. Hulihonua reminds us to be ready for the kuleana we are taking on in our lives, whether that’s having a child, entering a new job, embarking on a learning journey, or any other hana koʻikoʻi (important endeavor). When we are unprepared for big tasks but take them on regardless, hulihia (upheaval) can result.

To her union with Hāloa, Haumea brings herself as Hinamanouluaʻe, a Hina form that evidences the connection between these akua wahine. Hinamanouluaʻe evokes the image of thousands of organisms bursting into life, growing luxuriantly from the well prepared soil of the first union. The long breath of her kāne surely works in concert with her ability to manipulate water, cultivating the abundant flora and fauna that collectively make up our ecosystems and sustain us as kanaka. That is the generous gift of this relationship.

Hinamanouluaʻe could also speak to the endless growth and change native to motherhood and fatherhood. New parts of ourselves emerge all the time as we move through the journey of raising children—our evolution as parents demands it. Constant flexibility is the key so that we can continue to produce fruitfully, whether that be children or other creative contributions to the world.

With Waia, Haumea appears as Huhune, a name that speaks to all that is tiny, even particulate. Complex creations are made up of an infinite number of details that are impossible to see at first glance. It is only upon examination that the particulars become evident. Huhune reminds us of the importance of attention to detail and the value of noiʻi noelo (deep examination and sincere inquiry). Even the smallest things are important, for they contribute to the larger whole. And even though the little things can sometimes disappear into a bigger picture, the greater structure could not exist without them and they hold their own mana within it.

This name also recalls the many small tasks that fill the day when caring for young children, especially full-time. Millions of moments go into helping our children become who they are. Rather than reducing these to “minutiae,” makua Hawaiʻi have the kuleana of remembering what a beautiful privilege it is to birth and raise keiki, our most precious and treasured lei hiʻialo (garlands held to the bosom) gifted to us from our kūpuna in the Pō. Children build their understanding of life through countless small connections with the people who love and care for them and with the natural world (ʻohana akua) that sustains us all.

Haunuʻu is Haumea’s name in her relationship with Hinanalo. Haunuʻu speaks of mountain summits and large endeavors. Many small pieces must be put in place to reach a new height (all arranged on the solid foundation for growth established in the first two unions). When we’re in the midst of the myriad tasks required to build something we can be proud of, it can sometimes feel like walking up a steep mountain. Growth based on in-depth understanding and attention to detail (Huhune's gifts from the second phase) allows for the achievement of great things. Our most advanced structures such as loko iʻa, loʻi kalo, and heiau are made of many individual pōhaku all built up toward a higher function and purpose. The higher purpose of birthing aliʻi bloodlines is what your mea kākau believes Haumea was building towards through this progression.

Haunuʻu also brings to mind the ʻanuʻu or lananuʻu mamao, a type of tower on some heiau that was covered in kapa. Offerings were placed on the first level, which symbolized the earth. The second level symbolized the sky and lower heavens, and the third level the realm of the gods, where kahuna and aliʻi stood to communicate with the akua and access the higher realms. Hau is also the same as hahau, which means to offer a prayer or sacrifice. Perhaps another interpretation is that a sacrifice of time and energy is necessary in order to reach our goals (i.e. there’s no avoiding that trek up the mountain). What are we prepared to do to achieve something? Must we offer something up in order to receive the support we need?

Haulani is the name Haumea takes when she partners with Nānākāhili. This name can be interpreted in several ways. One meaning of Haulani is to be constantly on the move or restless. Haumea may appear this way as she goes back and forth between the lani and the honua. As mentioned before, many of our mele suggest that she left out of anger or perhaps dissatisfaction with her situation, which is certainly plausible, considering what transpired between her and Wākea. Restlessness can sometimes set in when family life is unharmonious. The pressure of an unhappy relationship during the busiest phase of life can, for some people, lead to discontent and the urge to flee. If the foundation of a relationship is unstable, or the hard, daily work of the prior phase was not attended to, those cracks will eventually find their way into the family.

However, your mea kākau would prefer to interpret Haumea’s frequent travel as a result of her constant quest for innovation and improvement, of her perpetual desire to level up. That theory supports the progression we have been building so far, with Haumea ultimately bridging the higher realms (lani) with the earth (honua) through creating aliʻi, who are both akua and kanaka at once—earthly manifestations and mouthpieces of the divine. Perhaps when she went away to those higher places, she was actively seeking new insights to benefit herself and her offspring upon her return. Maybe each of these unions was a way to imbue a new aspect of divinity into her creation. The practice of retreat is a rejuvenating process, a reminder that breaks away and time in different spaces can provide us with critical nourishment to continue our work, or even lead us to a much needed breakthrough.

Hīkāwaopuanaiea is the last of Haumea’s names in her final union with Wailoa. This name was the hardest for your mea kākau to interpret. It was given to her by Wailoa, raising the question of whether her other names were ones she chose for herself when she remade herself in the Haleopapa. Spellings of this name also vary widely across chants and stories, so pinning down any one meaning becomes problematic. Just as various schools have their own teachings, all of which are relevant, various spellings and meanings are possible simultaneously. Here, we will just look at one spelling from a couple of angles.

Perhaps, after her true identity was revealed, Haumea had a difficult parting with Wailoa that caused her to go unsteadily (hīkā) into a place of difficulty (wao puanaiea). Or maybe the wao puanaiea is a forested upland region where the ua puanaiea, a fine refreshing rain, falls gently, as suggested in moʻolelo and kanikau. It’s certainly more pleasant to think of her assuming this elemental form of a nourishing rain over the lush forests she helped create than it is to imagine her being “dried up” or “weak and sickly” as the dictionary definition of punanaiea offers.

Whatever the meaning, a possible theme in these interpretations is the waning of energy that happens with age. By this stage, Haumea had done a lot of work and birthed many children in her effort to connect the honua with the lani through the creation of aliʻi. Kiʻo was the final child in that project and Haumea may have been ready for another significant transition.

Image: Anianikū Chong

Image: Anianikū Chong

The term “hoʻokiʻo” means to cease menstruating. This is reflected in the line “papani ka wai o ke akua wahine” (the waters of the akua wahine ceased flowing) and is preceded by the deliberate drying up of her breast milk (“paʻipaʻi i nā ū”). In the Kumulipo version, we see the line “Pale ka maʻi, kaʻa ka lolo” meaning the genitals are blocked from producing and the brain engages. This speaks to Haumea moving into her “hānau ma ka lolo” phase where she births from the brain. Although she may have done this earlier in her story, at this point it likely became her primary means of creating. This can be seen as analogous to the third phase of womanhood, where wahine are done bearing children, but often produce some of their best intellectual work, as the resources that once went to nourish the ipu hoʻoilina (womb) are now free to nourish the lolo (brain), the home of the noʻonoʻo (the contemplative and analytical part of the intellect).

Haumea’s arc of creation and change illustrates that great work requires many revisions. If we are to innovate and evolve as humans, Haumea challenges us to continually transform our thinking, to not sink into tacit satisfaction with the status quo, and to regularly bring fresh energy and perspectives to what we are doing. This is the transformation she models for us as she cycles through, reaching higher and higher each time.

She also reminds us that we are part of a larger creative stream that flows eternally. We step into that stream when we work something through multiple iterations. Allowing ourselves to focus on process rather than product feeds our creativity as we continually shape and re-shape who we are and what we generate. The constructs of finality or perfection can sap our creative juices, whereas an abundance mindset of continual opportunities for change and improvement frees us up to explore and feel inspired.

The willingness to try over and over not only allows us to refine our creativity, but it also helps us to improve our relationships to each other and our living world, to Papa/Haumea herself. She is one of many kūpuna in a long line of deities, plants, animals, and people that allowed us to come into being and they represent our collective ʻohana. Learning how to be in right relationship with this ʻohana is in the interest of our own survival. Disrespecting Haumea and our collective ʻohana, especially if it means robbing from the future, can have disastrous consequences.

This is most evident in the story “No Ke Aʻo Hōkū,” which was penned by Kamakau. In this story, Haumea’s granddaughter is abducted by a selfish, cunning man and when Haumea can’t get her back, she retaliates in the extreme. Kamakau says, “There was only one thing left to do: take everything.” She takes away all the food plants and unleashes a massive drought. The night is as warm as the day, famine tears through the land, and nearly everyone perishes. This is the other side of Haumea that some folks might not be familiar with. She provides us with so much abundance, but she can also take it all away in one fell swoop.

Your mea kākau cannot speak for kāne, but would offer to wahine that in this larger project of restoring balance in the way we live on Papa/Haumea, one of our first lines of healing is to restore our aloha and mahalo for the river of ancestors that flows through us. Outside of when we hāpai keiki (carry a child in our womb), each month when we release the potential of an ancestor, we can let go of anything that is holding us back. We can send it down the river and make room for fresh potential.

That sort of release is a preferable alternative to bottling up frustrations or holding on to old, negative patterns until they erupt as another of Haumea’s forms—a moʻo niho wakawaka (a sharp-toothed lizard) that, when angered, can cause harm. Our built-in mechanism for cleansing allows us to keep fine-tuning who we are and how we live, but it requires the willingness to pause and take stock of our lives. It means continually building the self awareness, humility, and grace that helps us reflect, forgive, and release. And this, ultimately, allows us to be our most nurturing, fruitful selves.

The larger evolutionary lessons contained in Haumea’s names are haʻawina for everyone, but the regular flow of wai ʻula is the pathway for personal progress that Haumea has gifted wahine. Perhaps by offering directly back (hau) our red waters (mea) to her, we can build a pilina (relationship) that is mutually nourishing and prepares us to receive her gifts as we enter the final phase of womanhood: ka hānau ʻana ma ka lolo - birthing from the brain.

To contribute to this discussion, send ideas and feedback to kauamelemele@gmail.com

Mahalo to Shannon Wianecki and Nālani Wilson-Hokowhitu for the edits and rich discussions, and to Anianikū Chong for the stunning images. Check his work out at his website. E ola!

Visit Kealopiko Moʻolelo regularly over the coming months for more moʻolelo and mele that speak to the other designs in our series honoring Haumea.

Additional references and resources:

Kumulipo - A searchable, digital version published by Kamehameha Schools. Shows the six piʻo matings (lines 1944-1966).

Additional genealogy by P.S. Pakele - Shows the six piʻo matings and makes the connections between the generations clear.

Ea Mai Hawaiʻi na Kahakuikamoana - Another insightful genealogical mele.

Image: Hina Kneubuhl

Image: Hina Kneubuhl