Haumea & Hōkū

A story penned by Kamakau on the origins of navigation

Translated by Hina Kneubuhl

Haumea and the Star Space

For nearly a year, we've been honoring Haumea through a series of five designs - ua kualima ka hana. That process meant exploring several of her many aspects. While Haumea is most famous for fertility and productivity on the ʻāina, we believe that extends into the lani, or star space, as well. Just as she presides over the birthing of organisms on land, she is also involved in the birthing of stars in the heavens. Alongside many other akua, Haumea helps fill the sky space and set the seasonal and diurnal cycles. As she pervades both space and time, she wields her iʻe kuku (four-sided kapa beater), beating the kapa on which the world turns, and we see and feel her in the universal fabric that connects all life.

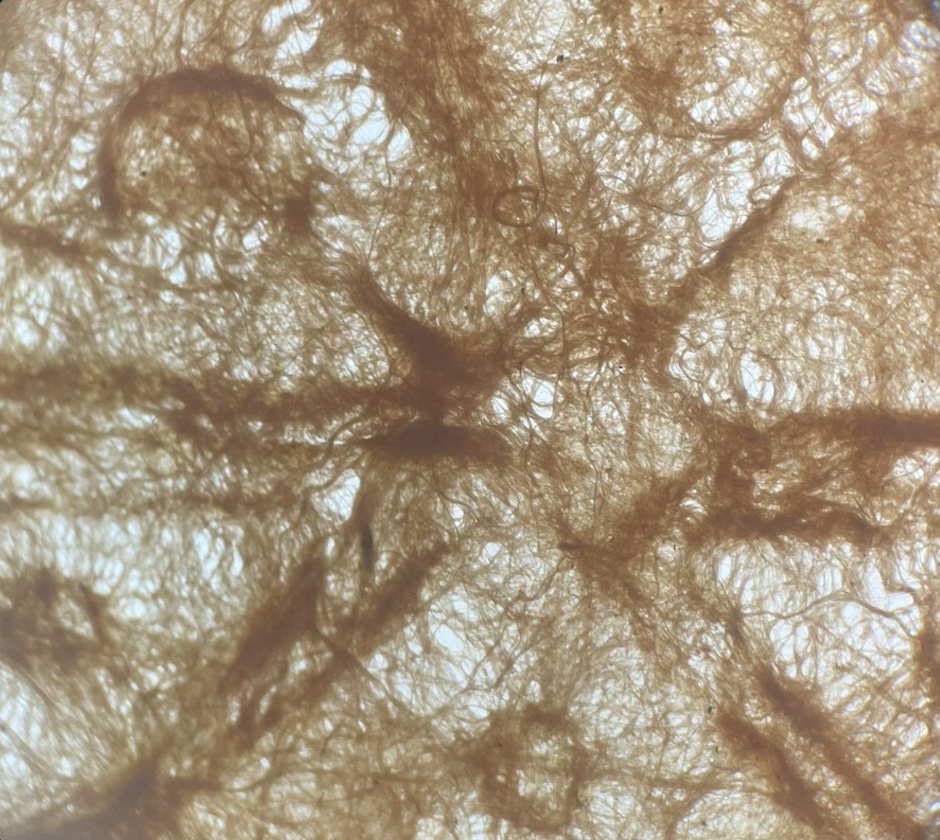

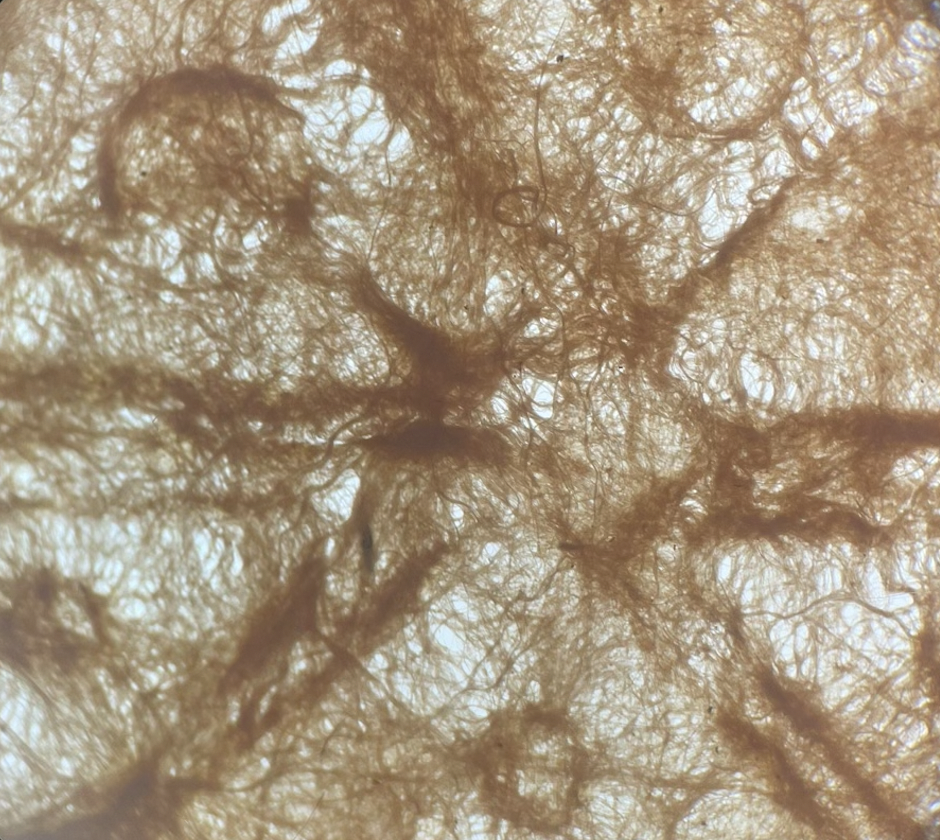

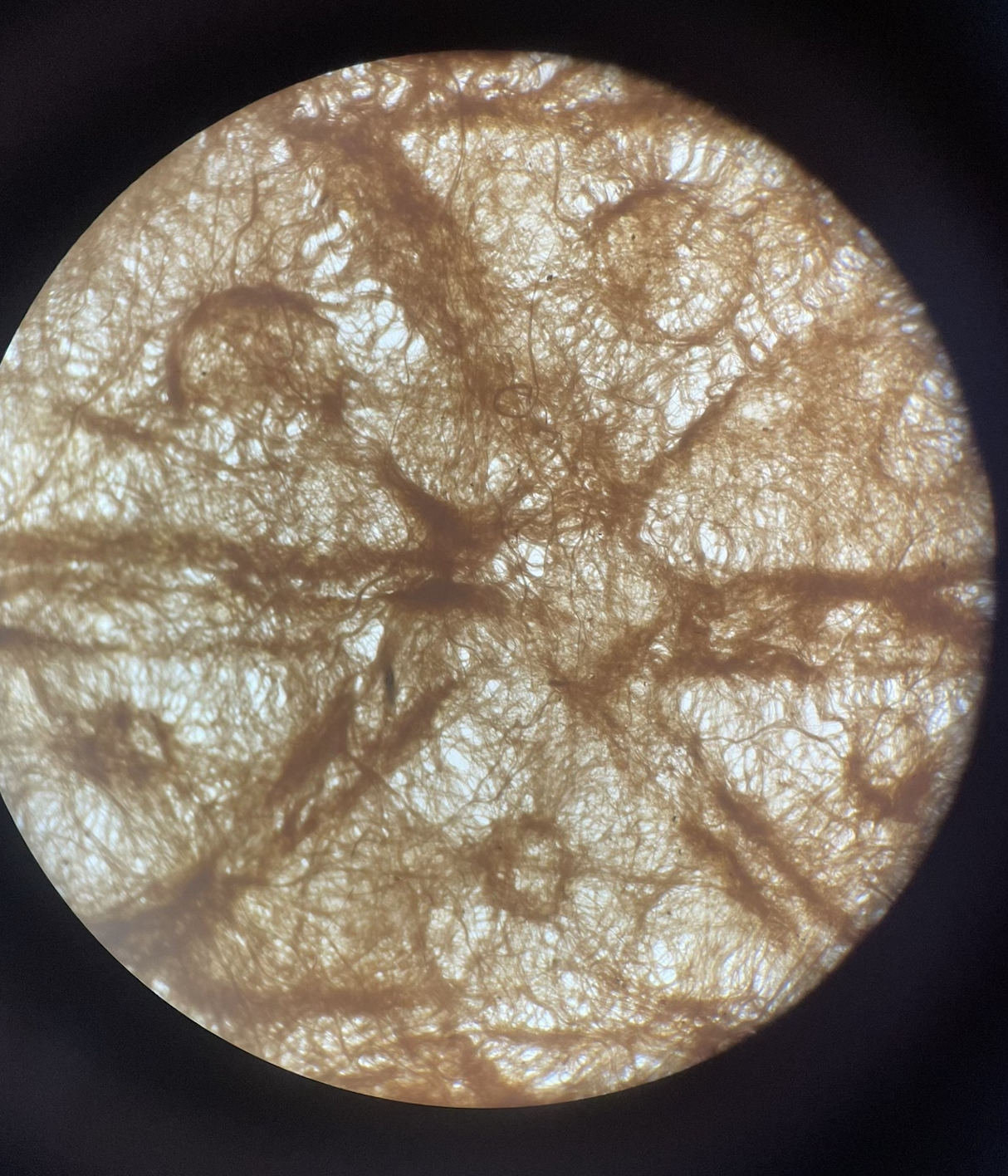

Fine kapa embossed with the pāwehe pūpū pattern. Photo by Hina Kneubuhl through the generous support of the British Museum's Benioff Oceania Program.

Fine kapa embossed with the pāwehe pūpū pattern. Photo by Hina Kneubuhl through the generous support of the British Museums Benioff Oceania Program.

This connection to the stars sets the perfect backdrop for this moʻolelo, No ke Aʻo Hōkū (On Navigation) which is the pani, or closing piece, for this season of Haumea that we have been navigating through. This story also highlights the fierce and destructive part of Haumea's nature, an aspect of this akua wahine we feel doesn't get enough air time. Here, we see it come forward as she forces kanaka to be creative and resilient.

Necessity is the mother of invention and Haumea is the great mother of all. This account shows us how she pushed our ancestors to a place where they had to recover one of the greatest technologies of all time: navigation.

This wasn't something she wanted to do, per se, but a punishment she was forced to exact on humanity after a selfish and short-sighted man committed a deeply harmful offense. His act of disrespect incurred Haumea's full wrath and the result was a powerful lesson: just as she can be the bearer of fertility, she can also be the harbinger of death. In this story, penned by Kamakau in 1865, Haumea initiates a massive, turbulent reset that forces kanaka to change, grow, and innovate. E nanea i ka heluhelu ʻana!

Note to readers: If you would like to read this story with ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi and English side by side, you will need to use a laptop or other full size screen. If you are viewing on a phone or an iPad, you will find the English below the ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi in each section. Mahalo!

Na ka nani kū mau o ka wahine lā e aʻo mai

No Ke Aʻo Hōkū

Na S. M. Kamakau

Honolulu, Iulai 26, 1865

Māhele 1

ʻO Pupūhuluana

1. ʻO ke kanaka makamua loa kēia i holo i Kahiki. ʻO ka ʻāina o (ʻAmerika), ʻo Oloimehani ka inoa. Penei hoʻi ke kumu i holo ai: I ka manawa iā Wailoa, Oʻahu, e hānai ana ʻo Wailoa i kāna moʻopuna, iā Kapahuʻeleʻele, i Hālawa; e noho ana kekahi kanaka i uka o Kaumana, ʻo Kulauka ka inoa, ua pilikia ʻo ia me kona kaikaina, me Kulakai.

2. Ua haku ihola ʻo ia i ke ʻie, a like me he manu lā ke ʻano, a ua hala nā makahiki ʻelima no kona hana ʻana ma ia mea; a ma waho aku, haku ihola ʻo ia i ka hulu. Ua hana ʻia nā kāula ma loko e huki ai, a laila ʻupaʻi nā ʻēheu, a hiki hoʻi ke lele me he manu lā.

3. Ua hala nō hoʻi ka makahiki ʻokoʻa ma kona hoʻāʻo ʻana i ka lele, a no kona ʻike ʻana nō hoʻi ua mākaukau ʻo ia no ka lele ʻana ma kahi lōʻihi, a laila kō kāna mea i hoʻokumakaia ʻia mai ai. Ua pilikia kona kaikaina, no laila kuko kona naʻau e loaʻa ka moʻopuna a Haumea iā ia, no laila kiʻi maila ʻo ia i Oʻahu, ua hele naʻe ua moʻopuna lā a Haumea i uka o Waipiʻo – Lelepua. Loaʻa ua moʻopuna nei a Haumea i laila, e hao aʻe ana ua manu kanaka nei, lilo.

4. A ʻike hoʻi ʻo Haumea i ka lilo ʻana o ka moʻopuna, e hao ana hoʻi ua wahi Haumea nei i kāna mau kauna lele a pau, ʻaʻole nō hoʻi o kū mai ua mea he lele. ʻO ka lele nō ia a komo i loko o ke ala polohiwa a Kāne, kokoke loa e loaʻa, e hoʻokuʻu iho ana ua manu kanaka nei i ka pōhaku. A ʻike ʻo Haumea i ka hāʻule ʻana iho o ka pōhaku, kuhi ihola ʻo ia, ʻo ka moʻopuna, e huli iho ana ʻo ua ʻo Haumea i lalo, alualu i ka pōhaku, ʻo ka loaʻa iho nō hoʻi ia, halulu ʻē ana i lalo. ʻO ia ka pōhaku Kapapaikawaluna.

5. A ʻike ihola ʻo Haumea ua puni ʻo ia ma ka hoʻopunipuni ʻia mai, no laila hoʻokahi hana i koe iā ia, ʻo ka lawe i nā mea a pau. E hao aʻe ana ʻo Haumea i ka ʻai a pau loa mai Hawaiʻi a Kauaʻi. Kuʻu iho ana nō kēia i ka pāpaʻa lā a maloʻo hoʻi ka ʻāina. ʻO ka ʻohana hoʻi a pau o ua Haumea nei, pau loa i ka hoʻihoʻi ʻia i Nuʻumehalani.

6. A hala akula ka ʻohana a pau o Haumea i Nuʻumehalani, a ma ia hope iho, ʻuʻu mai ana ka wī ma luna o ka ʻāina, ʻo ka hele hoʻi ia a hahana ua mea he wī; koʻehana ka pō me ke ao. Ua like nō hoʻi ka wela o ka pō me ke ao.

7. ʻAʻole kilokilo, ʻaʻole kahuna, ʻaʻole kāula e hiki ke hana a ke hoʻomaʻalili. ʻAi ka manu i kāna mau hua, ʻai ke kanaka i kona ʻohana iho. “Pili wale ka iʻa o Piliwale, ua hele ke kai, ka makamaka.”

On Learning Astronomy

By S. M. Kamakau

Honolulu, July 26, 1865

Part 1

Pūpuhuluana

1. He was the very first person to sail to Kahiki. The land know as America is called Oloimehani [by ka poʻe Hawaiʻi]. The following account is the reason Pūpuhuluana sailed there. When Wailoa [one of Haumea's many kāne] was an aliʻi on Oʻahu, he was raising his granddaughter, Kapahuʻeleʻele, in Hālawa. There was a man living inland of Kaūmana [Hawaiʻi] by the name of Kulauka and he and his brother, Kulakai, had a conflict.

2. Kulauka wove wicker into the shape of a bird and he worked on it for five years, plaiting the outside with bird feathers. Ropes were installed inside of it to pull on so the wings could be maneuvered and it could fly like a bird.

3. A whole year of testing flights passed and when he knew it was ready for a far flight, the instrument that would allow him to be avenged was complete. His younger brother was having problems, at which time Kulauka acted on his desire that Haumea’s granddaughter become his. So he came to get her on Oʻahu, but this offspring of Haumea had gone to the heights of Waipiʻo, to Lelepua. That's where he found Haumea's granddaughter, and he charged down forcefully in his bird glider, taking her.

4. When Haumea realised her granddaughter had been taken, she unleashed all of her aerial forms and there was no limit to her skills of flight. She flew up into the dark, glistening pathway of Kāne and just about caught Kulauka when he dropped a stone from his bird glider. When Haumea saw the stone plummeting and thought it was her granddaughter, she turned and flew downward, pursuing the rock, and when she caught it, she had already roared down far below. This is the rock known as Kapapaikawaluna.

5. When Haumea realized that she'd been duped, there was only one thing left to do: take everything. Haumea seized all food from Hawaiʻi to Kauaʻi. She released a great drought and the land dried up. Haumea’s entire family were all returned to Nuʻumehalani.

6. When Haumea’s whole family was safely in Nuʻumehalani, just after that a great famine tore through the land—one that became extremely severe. Both day and night were warm. The night was just as hot as the day.

7. There was no reader of omens, no priest or prophet who could stop it or make the heat abate. Birds ate their own eggs, people ate their own family members. “The fish of Piliwale clung on for dear life, for the water they needed to live had gone.”

Māhele 2

8. He kanaka ʻo Pūpuhuluana, a me Kapalakākiʻo no Kauaʻi, he mau koena lāua na ka wī; a he mau kānaka ikaika nō lāua.

9. E noho ana ma Kailua ʻelima kanaka, ʻekolu kāne a ʻelua wāhine. ʻO Olomana, ʻo Ahiki, a me Pākuʻi nā Kāne; ʻo Makawao hoʻi a me Hauli nā wāhine. ʻO kēia poʻe naʻe he poʻe kahu ponoʻī lākou no Haumea. Ua waiho iho nō hoʻi ʻo Haumea i mau wahi kāmau ea no lākou, ʻo ia hoʻi he kī a he pōpolo ma ko lākou ʻāina, ʻo Maunawili. He wahi kanaka māmā ʻo Pākuʻi i ke kūkini. ʻEono puni o Oʻahu i ka lā hoʻokahi.

10. He mau kānaka māmā ʻo Pūpuhuluana a me Kapalakākiʻo. I ka holo ʻana mai hoʻi o lāua nei a pae ma Waiʻanae, ʻaʻole naʻe he wahi ō o lāua. ʻO lāua wale nō hoʻi koe o Kauaʻi, no ka mea ua pau loa i ka make. Iā lāua nei hoʻi ma ke one o Waiʻanae, kū ana ʻo Pākuʻi. ʻIke akula lāua nei iā Pākuʻi, ʻōlelo wale ihola nō lāua nei iā lāua iho, “He kanaka nō kā hoʻi koe o Oʻahu nei.”

11. Iā Pākuʻi naʻe i hiki mai ai ma ko lāua nei wahi e noho ana, a hāʻawi akula i kona aloha iā lāua, a pēlā mai nō hoʻi lāua iā ia nei. Nīnau akula naʻe lāua nei, “He kanaka nō kā hoʻi koe o Oʻahu nei?” Hōʻole akula kēia me ka ʻī aku, “ʻAʻohe kanaka, ʻo wau wale ihola nō koe. ʻO kona manaʻo naʻe i hana aku ai pēlā, e hūnā ana kēia, me ka manaʻo hoʻi o pau ʻē auaneʻi kahi kāmau ea o lākou.

12. Nīnau hou akula nō ua mau kānaka nei, “Pehea Oʻahu nei i ka ʻai?” ʻŌlelo akula nō hoʻi ʻo Pākuʻi, “ʻAʻohe ʻai o Oʻahu nei, ua lawe nō ʻo Haumea i ka ʻai, i nā mea ulu, i nā hua ʻai, a me nā mea nō a pau, ua pau loa i ka lawe ʻia i Nuʻumehalani, a ua lawe nō hoʻi kēlā i kona ʻohana, a ʻo wau wale nō hoʻi koe lā, ua hoʻonoho ʻia iho nei au i kiaʻi no ka ʻāina nei, a loaʻa wale maila iā ʻolua.”

13. Nīnau hou akula nō ua mau kānaka nei, “Pehea lā hoʻi ʻo Maui a me Hawaiʻi, he ʻai nō paha ko laila a he kanaka nō hoʻi paha e ola ana?” ʻŌlelo akula ʻo Pākuʻi, “ʻAʻohe akula nō he ʻai, loaʻa aʻe nei kā hoʻi ka wī i kuʻu ʻāina, ʻo ke one lauana kēia, he liu ma lalo aʻe. ʻAʻole nō hoʻi he kanaka o ka hikina koe, no ka mea he liu iho ko laila ma luna. Ua lawe ʻo Haumea i ka ua a koe i ka lihilihi o ka lehua.” Pane hou akula nō kēia, “Ma kai nō hoʻi paha ʻo ʻolua?” “ʻAʻole, ma uka nei nō māua, i ʻike ʻia aku hoʻi kēia wahi aku.” Makaʻu ihola naʻe kēia o loaʻa kahi ō o lākou nei.

14. Holo aku ana ʻo Pākuʻi, e holo aku ana nō hoʻi lāua nei, haelehaele ua mea he māmā o lākou nei. A hiki lākou nei ma ʻEwa, ʻo ka waiho nō o ka ʻāina, ʻo ke kū nō o kauhale, ʻo ka hele nō a ka puaʻa a me ka moa, ʻaʻole naʻe he kanaka, ua pau i Mānā, ua haohia e Kaiuʻilei, ua pau.

15. ʻO ko lākou nei holo maila nō ia a Leilono, holo mai ana ke ʻala o ka pōpolo, a iho i Waikoaʻe a Kalaepōhaku. ʻŌlelo maila ua wahi kanaka nei, “Eia ke alanui lā ma kai o Makaaho, a hiki aku ma Makapuʻu."

16. Hōʻole akula nō lāua nei me ka ʻī aku nō hoʻi, “E aho māua ma uka o Nuʻuanu, ʻakahi nō kā hoʻi ka holo mai nei o ke ʻala o ka hākai pōpolo.” Pane akula nō ua wahi kanaka nei ma ke ʻano hūnāhūnā, “ʻAʻohe ʻai o Koʻolau, ʻaʻohe nō hoʻi he kanaka, a ʻo ke ʻala hākai pōpolo a ʻolua e honi lā, he pua kāmakahala ia no Nuʻuanu, paʻia aʻela e ka ʻahihi, pohole ka pua i ka makani, i ka hoʻoluli ʻia e ke Kiʻowao, kuhihewa ai ka malihini he ʻala no ka hākai pōpolo.”

17. ʻŌlelo maila ʻo Pākuʻi, “ʻAuhea ʻolua, e kala mai ʻolua i koʻu hewa, no ka mea ua kauoha ʻia au e kiaʻi i ka ʻāina, ua hāʻawi mai hoʻi ʻo Haumea i wahi kāmau ea no mākou, ʻaʻohe kanaka e māʻalo i ko mākou wahi, akā, na ke Akua mai nei hoʻi ko ʻolua ola ʻana.” A hoʻomaikaʻi akula lāua nei me ka ʻī aku, “E ola hoʻi hā ʻoe i ke Akua.”

Part 2

8. Pūpuhuluana and Kapalakākiʻo were men from Kauaʻi—survivors of the famine—and they were strong individuals.

9. Five people were living in Kailua, three men and two women. Olomana, Ahiki, and Pākuʻi were the men, Makawao and Hauli were the women. These people were Haumea’s own attendants. Haumea left them some foods on which to survive, specifically kī and pōpolo, on their land in Maunawili. Pākuʻi was a fast runner. He could complete six circuits of Oʻahu in a single day.

10. Pūpuhuluana and Kapalakākiʻo were also fast men. When they sailed here and landed in Waiʻanae, they had no rations. They were the only ones left on Kauaʻi, as everyone else had perished. Once on the shores of Waiʻanae, they saw Pākuʻi and said to themselves, “There is someone left here on Oʻahu.”

11. Pākuʻi made his way to them, gave his regards, and they did the same. The two of them asked, “Are there survivors here on Oʻahu?” He denied this, saying, “There is no one except me left.” However, the reason he acted that way was to be secretive, thinking perhaps their remaining food would be quickly eaten up.

12. These two men inquired once more, “What about food here on Oʻahu?” [Pākuʻi answered,] “There is no food here on Oʻahu, Haumea took the food, the plants, the fruits, and everything, it has all been taken to Nuʻumehalani. She took her family as well, and only I remain; I have been appointed as a guardian for this land, and now the two of you have found me.”

13. These men asked again, “What about Maui and Hawaiʻi, might there be food or survivors there?” Pākuʻi said, “There is no food, as my land was overcome by famine. These are vast sands with brackish water below. And there is no one remaining on the east side, for there is only brackish water above ground. Haumea took the rain and only the tiniest bit is left in the lehua blossoms.” He spoke once more, “Will you two stay here by the ocean?” [They replied,] “No, we shall go upland to see what places lie ahead.” Pākuʻi was afraid, however, that these two would find their food.

14. Pākuʻi took off running and these two ran behind him, all of them running at a fierce pace. They reached ʻEwa and the land lay before them, groups of houses standing prominent, the pigs and chickens running about, but there were no people. They had all gone off to Mānā, taken by Kaiuʻilei, gone.

15. Then they ran to Leilono, the smell of the pōpolo coming to them. They descended to Waikoaʻe and on to Kalaepōhaku. Pākuʻi said, “The road goes below Makaaho on to Makapuʻu.”

16. The two of them refused, saying, “It is better for us to go up into Nuʻuanu, we just smelled the fragrance of pōpolo being cooked.” Pākuʻi responded furtively, “There is no food in the Koʻolau region, there are no people, and the scent of pōpolo cooking that you two smell, that’s the the kāmakahala blossoms of Nuʻuanu that have been struck by the ʻahihi branches, the flowers bruised and tossed about by the Kiʻowao wind, giving newcomers the wrong idea that it's the scent of pōpolo cooking.”

17. Then Pākuʻi said, “Listen, I ask the two of you to forgive my wrong, for I was charged with guarding this land, and Haumea gave us some sustenance to survive on. No one has come past our place, but the gods have clearly allowed you two to survive.” The two of them were thankful and said, “May you live by the grace of the gods.”

ʻO ʻoe ia, e Haunuʻu, e Haulani

Māhele 3

18. I ka hiki ʻana o lākou nei ma kauhale, ua moʻa aʻe ka hākai pōpolo, e kōwī mai ana, a hāʻawi ʻia maila iā lāua nei ʻeono pōpō, a ʻehā paukū kī, e hao aʻe ana nō lāua nei, pau. A hāʻawi hou maila nō, e hao aʻe ana nō lāua nei, pau nō. A hāʻawi hou maila nō, e hao aʻe ana nō lāua nei, pau nō.

19. ʻŌlelo maila hoʻi ʻo Olomana, “ʻO nā ikaika o ʻolua a, e kiʻi ʻia i ʻai na kākou i Ololoimehani, i ka ʻāina o Makaliʻi, loaʻa ka ʻai a kākou, a ola kākou. “He loaʻa nō,” wahi a Pūpuhuluana, “ke kuhikuhi ʻia nō hoʻi paha a maopopo, a na wai hoʻi e ʻole ka loaʻa.”

20. ʻŌlelo hou mai nō hoʻi ʻo Olomana, “E moʻa nō ke kī na kākou i kēia lā?” “He moʻa nō hoʻi paha,” wahi a ka malihini. “ʻO kahi kī hoʻi hā ma mua,” wahi a kamaʻāina. “ʻO ka umu paha ma mua, he mea lōʻihi auaneʻi ke kī ke maopopo nō hoʻi kahi i ulu ai.” Pēlā aku ʻo Pūpuhuluana. He hopohopo naʻe ko ka poʻe kamaʻāina o ʻenaʻena ʻē ka imu, ʻaʻole hoʻi e loaʻa koke ke kī.

21. A pau kā lākou kamaʻilio ʻana, e hao aku ana ʻo Pūpuhuluana, ʻā ka imu, e hao aku ana nō hoʻi kēia i ka uhuki i ke kī, kū ke āhua o ua mea he kī. ʻIke akula ka poʻe kamaʻāina, hoʻōho aʻela lākou me nā leo nui, e ʻī ana, “Auē! Auē!! Auē ka make ē!!!” Kainō paha ʻo kahi kī mai nei ʻo ka pono. Eia kā, he hana hoʻohuakeʻeo loa nō. Pane hou maila nō hoʻi ʻo Olomana, “E hiki auaneʻi iā ʻoe ʻo Kūmakalehua, he ʻōhiʻa nui loa i ka nuku o Nuʻuanu, kahi i kū ai.” E hao mai ana ʻo Pūpuhuluana, ʻo kumu, ʻo ka lau, kū i Kailua.

22. “E kālai [i] kēia lāʻau i kiʻi, e hoʻohālike me nā lawaiʻa a Makaliʻi, ʻo ʻIeʻiea, ʻo Poʻopalu.[”] Ua hana ʻia a kuapuʻu e like me ke kanaka lawaiʻa kākā uhu, kuʻi i ka lauoho, paʻa i ka maka pipi, mākaukau nā mea a pau.

23. ʻŌlelo aʻo aku ʻo Olomana iā Pūpuhuluana, Pākuʻi, a me Kapalakākiʻo, “ʻO ʻoukou ke holo i Olomehani i ka ʻai i kumu hoʻolaha; i ʻuala, i kalo, maiʻa, kō, ʻape, kī, uhi, pia, piʻa, hoi, pala, hāpuʻu, ʻāmaʻu, kūpala, niu, ʻōhiʻa, ʻulu a me nā meaʻai a pau, me nā mea hua a pau. I ko ʻoukou holo ʻana a loaʻa ʻo ʻIeʻiea a me Poʻopalu, e kamaʻilio pū ʻoukou ma kaʻu kauoha, a e haʻi aku hoʻi ma kuʻu inoa.”

Holo ana i Kahiki

24. (No ka Moʻolelo Hawaiʻi kēia moʻolelo, e pili ana i ke akamai a me ka naʻauao o ko kākou poʻe kūpuna i ka holo moana, i ka nānā hōkū. Na kākou iho e hoʻokaʻawale i kahi o ke akamai a me kahi o ka wahaheʻe, no ka mea ua ʻoi ko ʻoukou ʻike, ko ka poʻe hou.)

(ʻAʻole i pau.)

Part 3

18. When they reached the compound, the pōpolo had finished cooking, the moisture was being squeezed out, and the two of them were given six balls and four sections of kī, which they completely devoured. They were given some more and devoured that. They were given portions once more and the two of them ate it all up.

19. Olomana said, “Because the two of you are so strong, you should go and fetch food for us in Ololoimehani, in the land of Makaliʻi, where our food will be found, and we shall survive. “Surely we can find it,” replied Pūpuhuluana, “If given clear directions that are understood, who wouldn’t find it?”

20. Olomana spoke again, “Will there be kī cooked for us today?” “Maybe there will be,” said the newcomer, Pūpuhuluana. “Well we need the kī first,” said the local. “Perhaps we should make the oven first, for the kī is probably far away if you know where it grows.” That was Pūpuhuluana’s response. The locals were worried, however, that the oven would be hot and ready and the kī would not be quickly procured.

21. When they were done talking, Pūpuhuluana swung into action and the oven was alight. He worked energetically, pulling up the kī, a great pile of it heaping up. The locals saw what was happening and exclaimed loudly, “Oh! Oh no!! Death!!!” One would think the kī was the thing going into the imu. Instead, there was this terribly cruel joke [that Pūpuhuluana would be cooked]. Olomana spoke again, “Perhaps you will be able to get Kūmakalehua, the massive ʻōhiʻa that stands at the entrance to Nuʻuanu.” Pūpuhuluana used all his might and the tree, leaves and all, appeared in Kailua.

22. [Olomana told him] “Carve this tree into figures that look like ʻIeʻiea and Poʻopalu, the fishermen of Makaliʻi.” They fashioned humpbacked figures that resembled uhu fishermen, and they put hair put on their heads and pipi shells in for their eyes. Everything was ready.

23. Olomana said to Pūpuhuluana, Pākuʻi, and Kapalakākiʻo, “You three shall sail to Olomehani to get starts of food plants—for sweet potato, taro, banana, sugar cane, ʻape, kī, pia, piʻa, yams, hāpuʻu fern, ʻāmaʻu fern, coconut, mountain apple, breadfruit, and all foods and fruits. When you sail and find ʻIeʻiea and Poʻopalu, you all tell them of my order, and tell them my name."

Sailing to Foreign Lands

24. (This story is from the Hawaiian History series and is about the acumen and wisdom of our ancestors in sailing and astronomy. It is for us to separate the intelligent parts from the lies, as you all, the people of today, have greater knowledge.)

(To be continued.)

He Kālaimanaʻo ʻAna

Sadly, your mea unuhi nei (translator) was unable to find the next instalment of this moʻolelo. Perhaps the koena (remainder) is out there somewhere and will surface in time. This first part, however, is packed with potent lessons and full of food for thought.

Many parallels can be drawn between this story and modern times. We are living in an era where technology is increasingly used for harmful or selfish intentions, often leading to chaos and suffering. Kulauka used the technology of flight to disrespect Haumea (Papa) and robbed from the future by stealing her granddaughter, an eerie parallel to the modern day abuses of the planet that are bringing about climate change, effectively looting the resources of future generations.

Additionally, chasing his selfish pursuit through technology led not only to Kulauka's own demise, but to the loss of much of the accumulated ʻike (knowledge) of his people. It was from this place of surviving crisis that they had to regrow voyaging practices in order to retrieve all the important food plants. We see them turn immediately to the carving of kiʻi (images of akua or ʻaumakua) as a first step in this process.

As bleak as this story may present at first read, there is hope to be found in its words. These ancestors of our distant past actually managed to recover the knowledge they needed and got the food plants back again, for had they not succeeded, we would not have this story in our hands today. Their lessons are sobering ones, however, and the ones mentioned here are just a few of the insights this moʻolelo has to offer. As new ones present themselves, please reach out and share them with your mea unuhi by sending an email to kauamelemele@gmail.com where you can also send feedback on translations or call out any errors you see.

A huge mahalo and aloha goes out to my kumu unuhi, Puakea Nogelmeier, who gave feedback on the first version of this translation, and to my colleagues at awaiaulu.org - nui ke aloha iā ʻoukou a pau.

MAHALO NUI!